Almost the Same Everywhere: San Gallery’s Inaugural Exhibition

Written by Yu-Chang Shen

“Almost the Same Everywhere” is a renowned Chan Buddhist koan first documented in the *Recorded Sayings of Chan Master Fenyang Wude*. This koan originates from a dialogue between Chan Master Wuzhuo, a Tang dynasty monk visiting Mount Wutai, and an elderly man. The old man first inquired about how the temples in southern China were maintained and the number of monks in each temple. Chan Master Wuzhuo replied that few monks adhered strictly to the rules, with temples housing between 300-500 monks. When Wuzhuo reciprocated the question, the old man described his temple as a place where “saints and common folk coexist, with dragons and snakes intermingling,” and the number of monks was “almost the same as in other temples everywhere.”

Visitors to San Gallery might similarly wonder, “What is exhibited in this gallery? How many artists are represented here?” The response from San Gallery mirrors that given by the old man at Mount Wutai, which is “almost the same as in other galleries everywhere.” This response doesn’t provide specific details because the question itself seeks a deeper, more absolute truth, which the original inquiry bypasses.

So, how do we grasp this absolute truth? Roland Barthes suggests in his book *L’Empire des signes* that freedom from the possession of meaning is one effective method. Understanding this approach could help San Gallery provide us with genuine answers. Fifteen artists have been invited to the exhibition “Almost the Same Everywhere” to showcase the current state of visual arts in Taiwan and Japan.

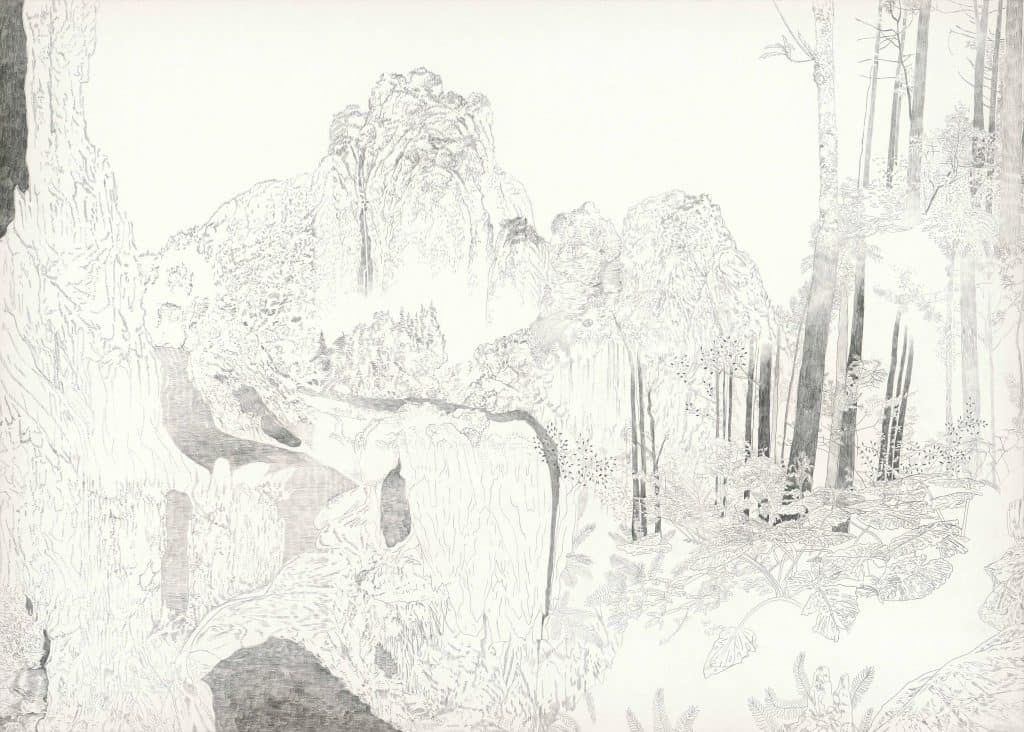

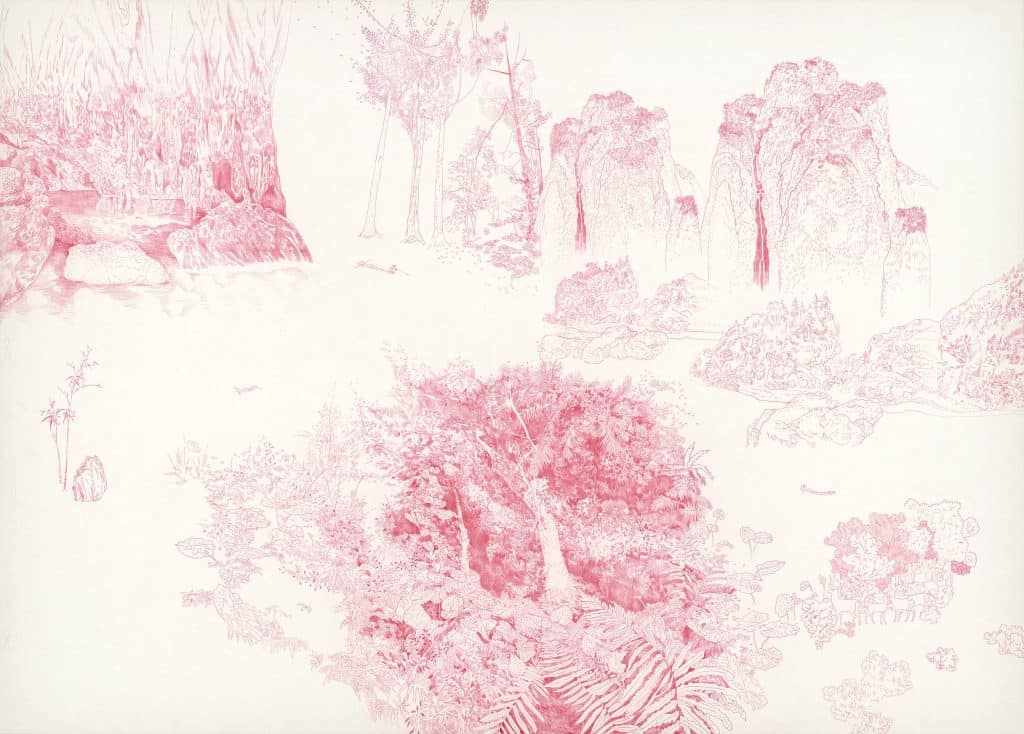

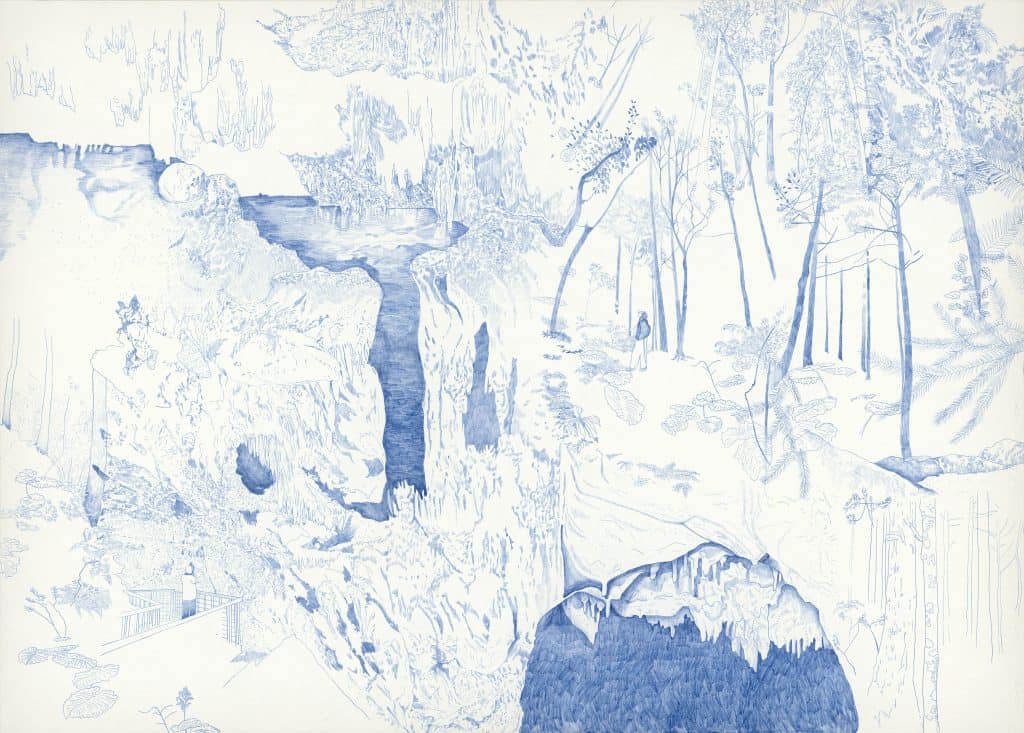

Yong-Ning Tzeng transforms linear time from written works into generative universe time using vibrant lines that radiate from the center to the edges of indistinct color forms on paper. Ya-Ting Kao employs carbon paper to transcribe visions and images, blending scenes and landscapes into discontinuous dream-like visions with vast gaps among various spacetime densities. Jui-Chien Hsu manipulates linear industrial materials, light yet strong like construction materials, to craft intricate layouts akin to a crime scene, allowing the objects to pry open cracks of meaning in their referential interactions.

Yu-Ning Yang excels at creating a grainy, foggy texture with fleeting strokes on sensitive raw Xuan paper, reminiscent of a photographic negative’s development. Ai Makita reimagines urban landscape components—plastic and metal—as vital tissues, prompting contemplation on the boundary between artificial and natural objects. Liang-Cherng Chiow’s sculptures evoke images of bent metal construction materials or die-cut iron sheets, attempting to construct open spaces on alienated terrains using pottery clay.

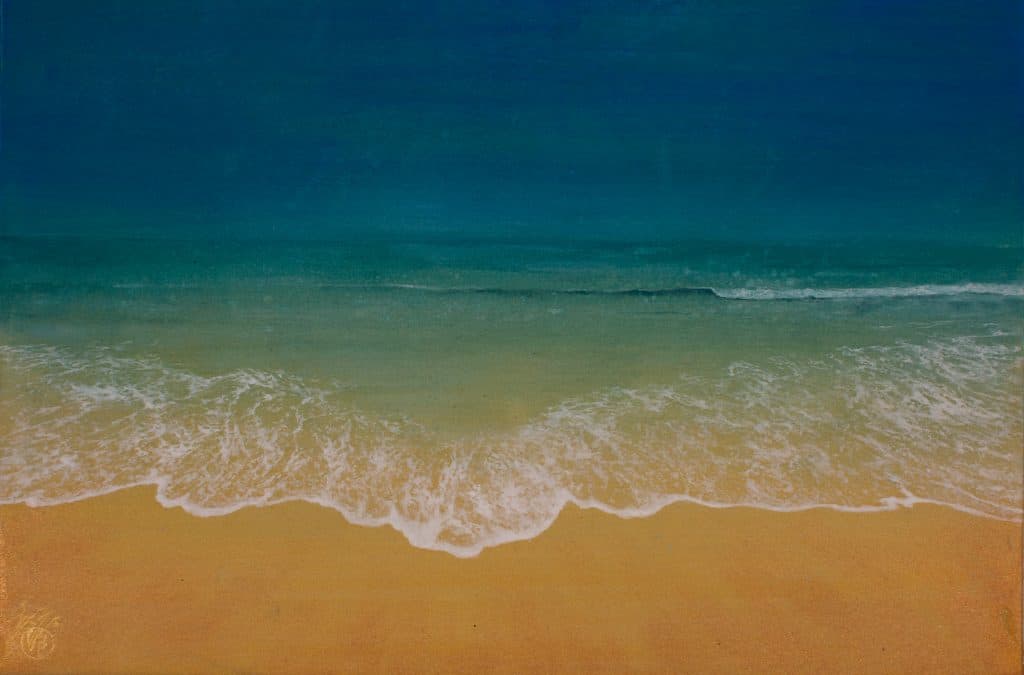

Fan-Hsuan Hsu depicts oceanic scenes on Kochi hemp paper using mineral pigments, where wave foams interspersed with starry lights reflect a sky distorted by undulating waves. Sheng-Hung Shiu reconfigures photos from mountain hikes, blending personal landscape experiences with digital memories to create a dialectic scene between visual information and painterly thought. Zung-Lung Tsai uses glazed pottery clay to preserve the hard-edged creases and bulging volumes of paper crumpled into a ball, causing smooth, flat surfaces to collapse or transform into bent objects.

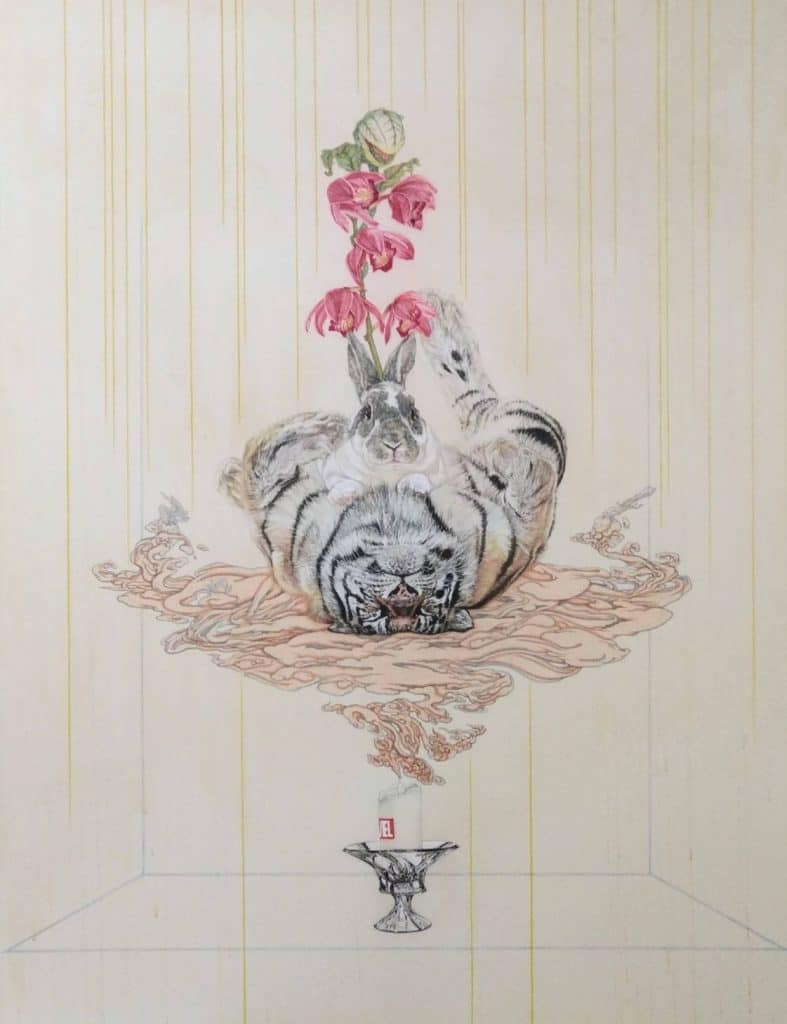

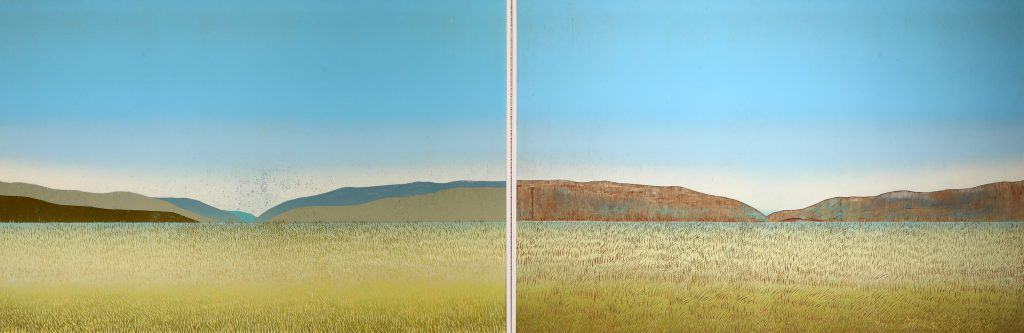

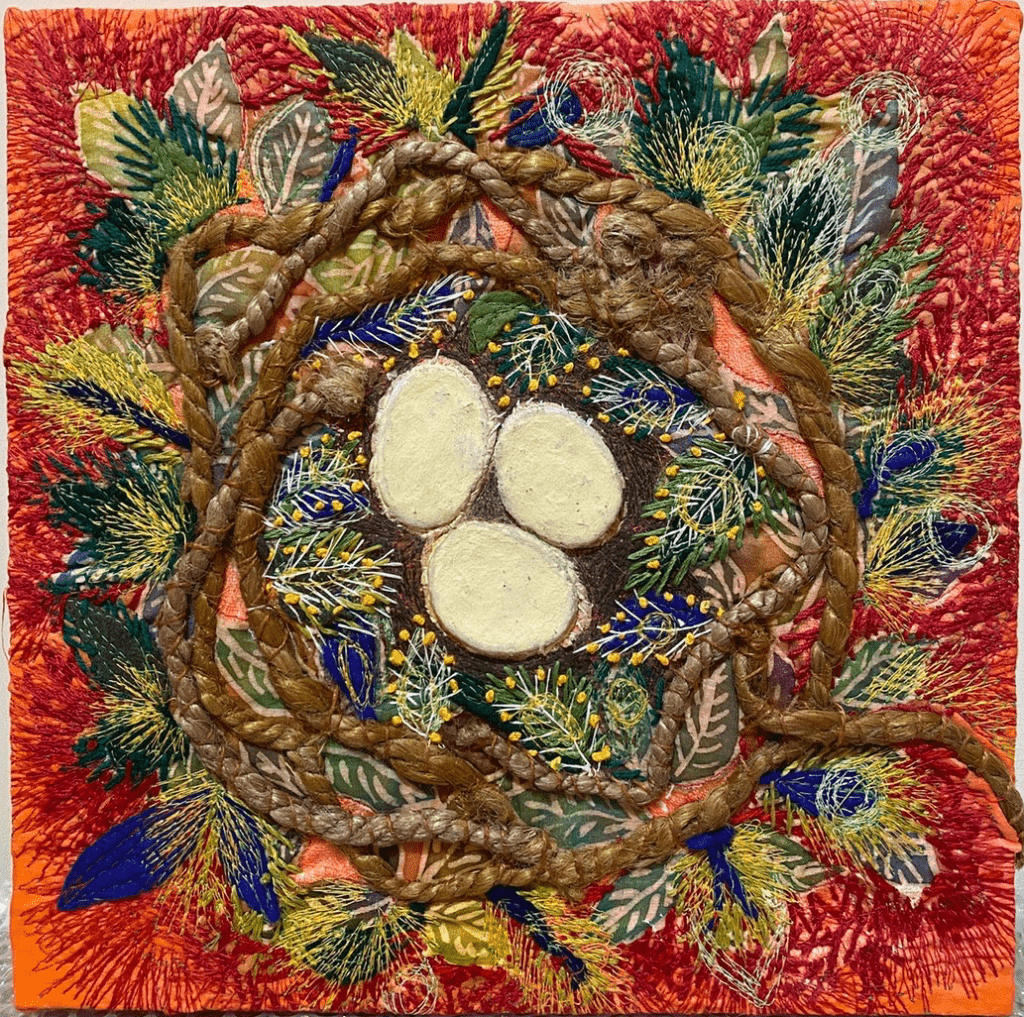

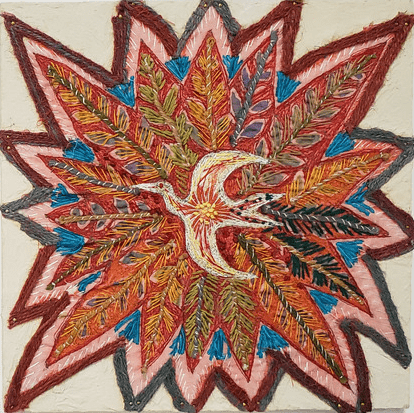

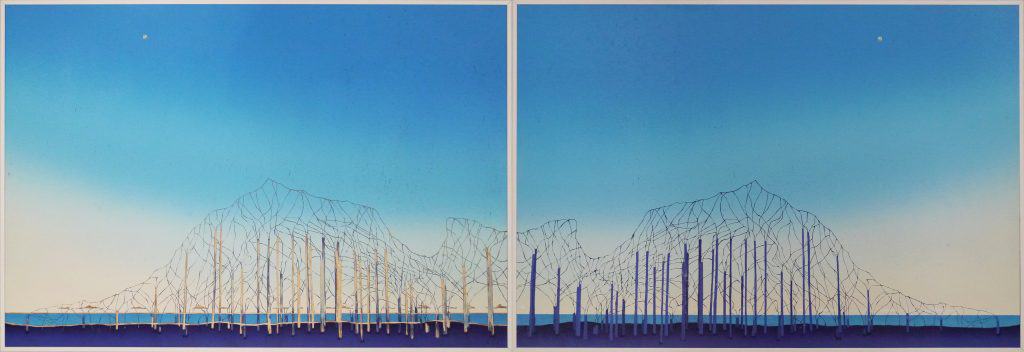

Ping-Yi Li embarks on a journey of self and homeland discovery post-pandemic, assembling woodcuts and wood plates to create dialogic mirror image sceneries. Jessica Tao positions images of animals within the consumer landscape of contemporary daily life, embedding a quiet elegance with an undertone of absurdity and dissonance in her works. Mariko Kobayashi utilizes various fiber art techniques—weaving, dyeing, embroidery—to depict diverse life forms, symbolizing life’s cyclical nature.

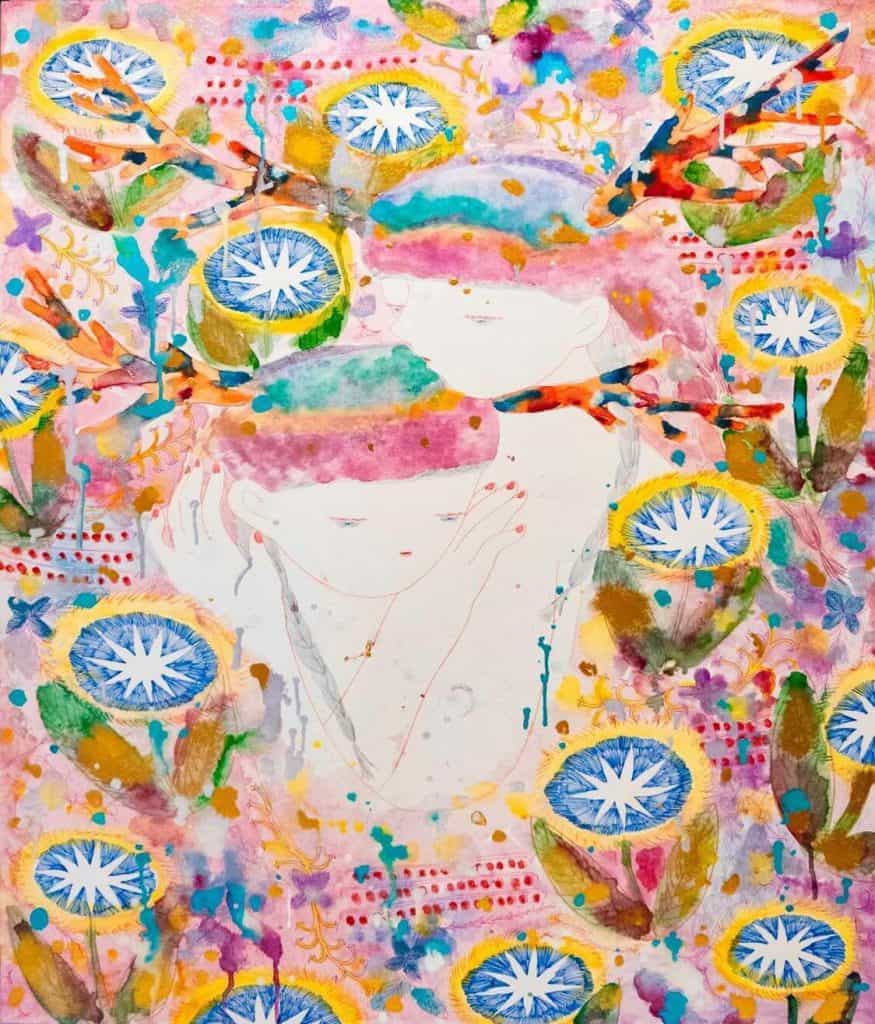

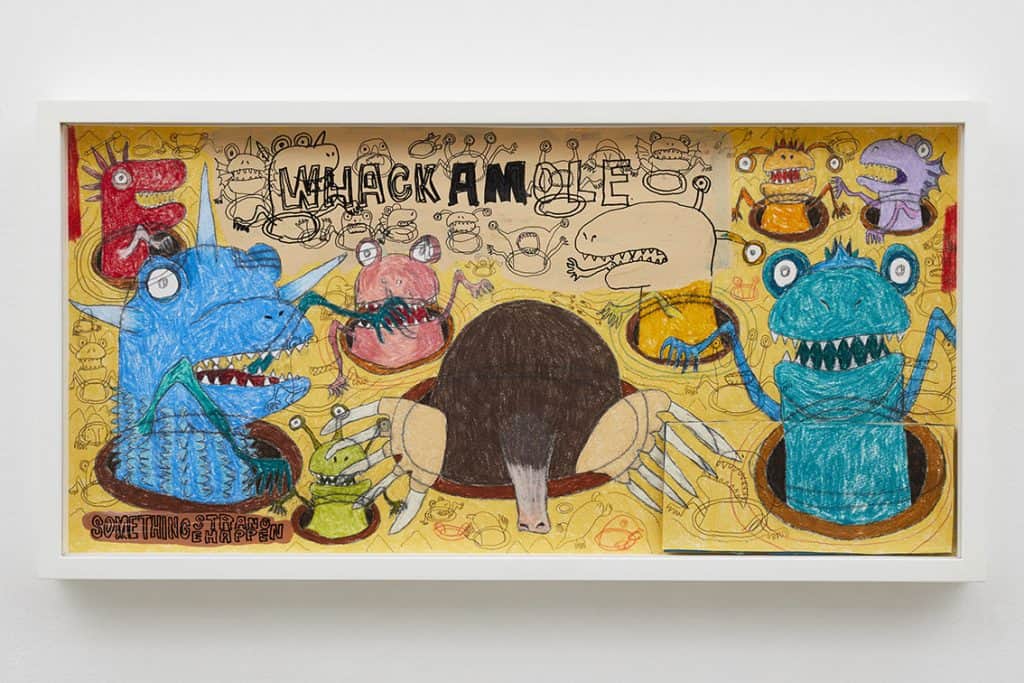

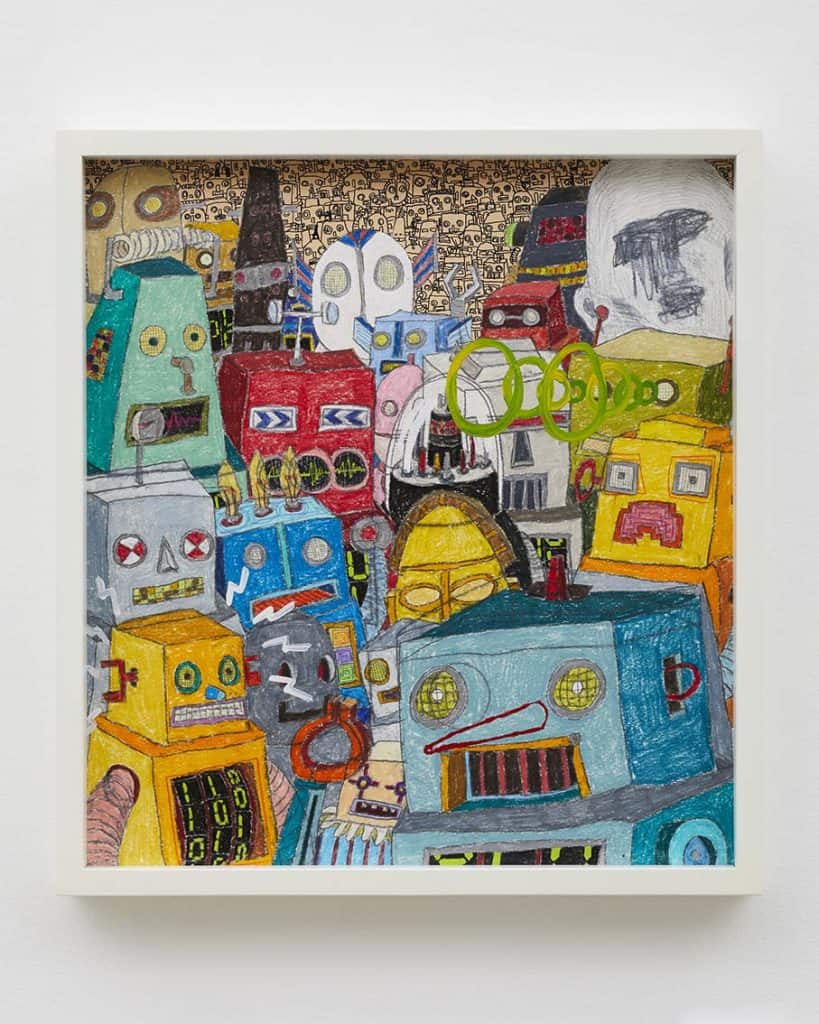

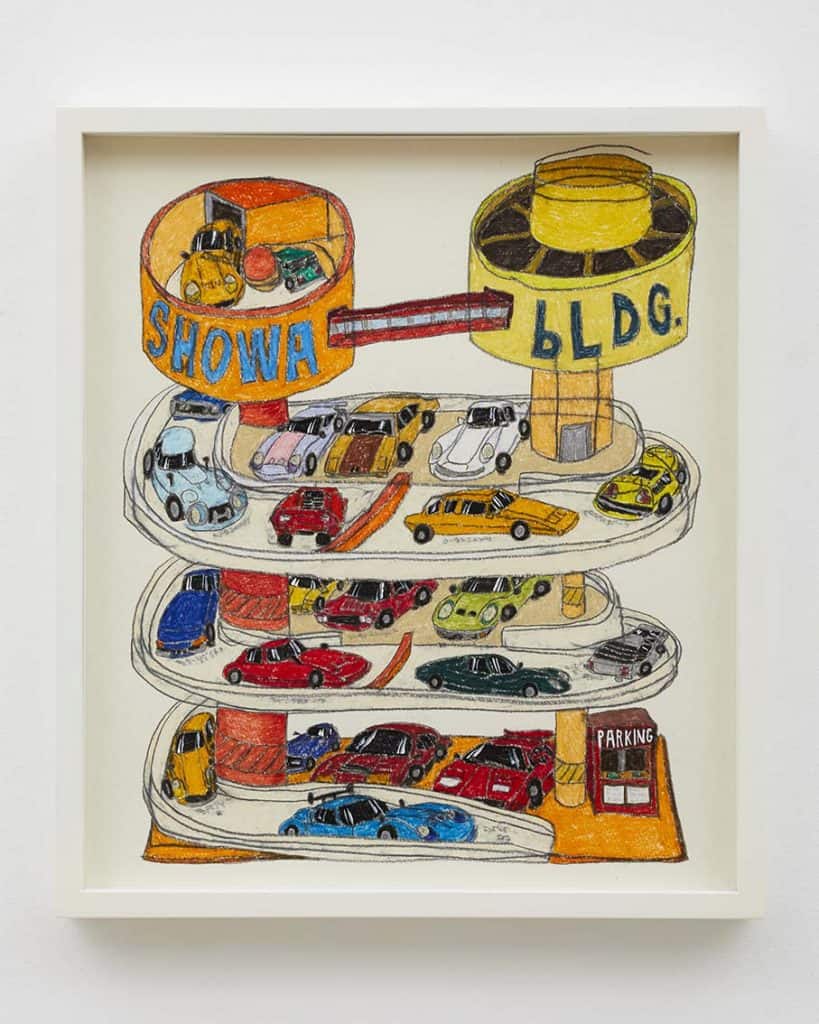

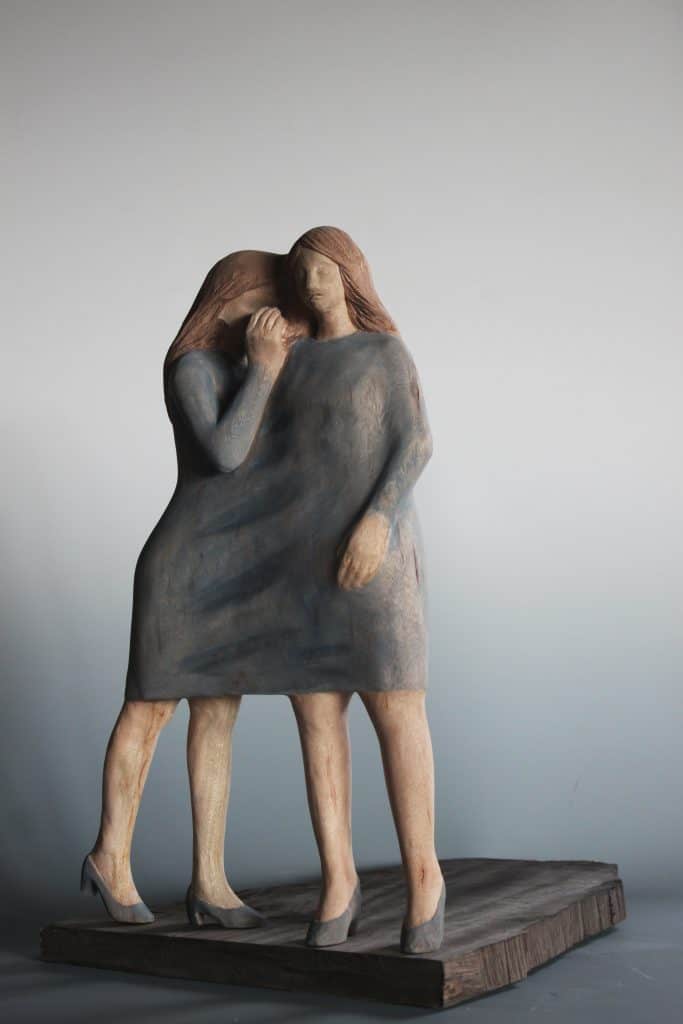

Shintaro Miyake crafts an array of brightly colored, endearing, dreamy characters on paper that articulate his social observations. Atsuko Yamashita continues to explore her inner fantasy world on washi paper, spreading her iconic images across thin, translucent colors like a blur of imagination. Yu-Tung Lin carves closely interconnected yet emotionally torn figures from wood, probing the nuances of love and intimate relationships.

The exhibition showcases common themes among contemporary artists in Taiwan and Japan, addressing changes and flows in space, the blending of digital images with physical landscape experiences, and the reflection of individual consciousness through mirrored sceneries. This opening exhibition, named for a Chan koan reflecting the pervasive similarities across diverse settings, symbolizes Taiwan’s boundless potential and San Gallery’s commitment to fostering dialogue and exchange among artists of different generations and nationalities, aiming to present Taiwanese art across generations to a diverse collector base.

Almost the Same Everywhere: The Opening Exhibition of San Gallery

Written by Yu-Chang Shen

“Almost the Same Everywhere (前三三,後三三)” is a very famous koan (dialogue, question) in Chan practice that is first recorded in the Recorded Sayings of Chan Master Fenyang Wude (汾陽無德禪師語錄). This koan was originally the dialogue between Chan Master Wuzhuo, who was a monk in the Tang dynasty visiting Mount Wutai, and an old man. In the dialogue, the old man first asked Chan Master Wuzhuo how were the temples in southern China maintained and how many monks were there in a temple? Chan Master Wuzhuo said that few monks abided by the rules, and there were 300-500 monks in a temple. And then Chan Master Wuzhuo asked the old man how was the temple here maintained and how many monks were there? And the old man said that “saints and common people dwell together, and dragons and snakes intermingled.” The number of monks there was “almost the same as in other temples everywhere.”

Perhaps we would like to ask questions like “What are exhibited in this gallery? From how many artists the works here are?” when we visit San Gallery for the first time today. The answer given by San Gallery is the same as the one given by the old man at Mount Wutai, which is “almost the same as in other galleries everywhere.” It is not answering the question in a specific way because the question is not asking for the absolute truth. Therefore, the original question is omitted, and the reply is the answer to the absolute truth. But how can we know the absolute truth? There is an effective way proposed by Roland Barthes in his book L’Empire des signes: to be free from the possession of meaning. If we know this way, then San Gallery may be able to give us the answer. Fifteen artists are invited to participate in the exhibition “Almost the Same Everywhere” to present the nowadays appearances of the visual arts in Taiwan and Japan with their works.

Yong-Ning Tzeng expands the linear time existing in written works into generative universe time with the use of colorful lines which fill indistinct color lumps from the center to the edges on the paper. Ya-Ting Kao uses carbon paper to print her script which transcribes visions and pictures, merging scenery and landscape painting into jump-cut landscapes like visions in dreams that have huge gaps among different space-time densities. Jui-Chien Hsu takes linear industrial objects which are light and strong like construction materials and designs a delicate layout like a crime scene, making the objects open the crack of meaning in their interactive reference. Yong-Ning Tzeng, Ya-Ting Kao and Jui-Chien Hsu respectively send linear signals in their own ways in the attempt to detect consciousness and meaning.

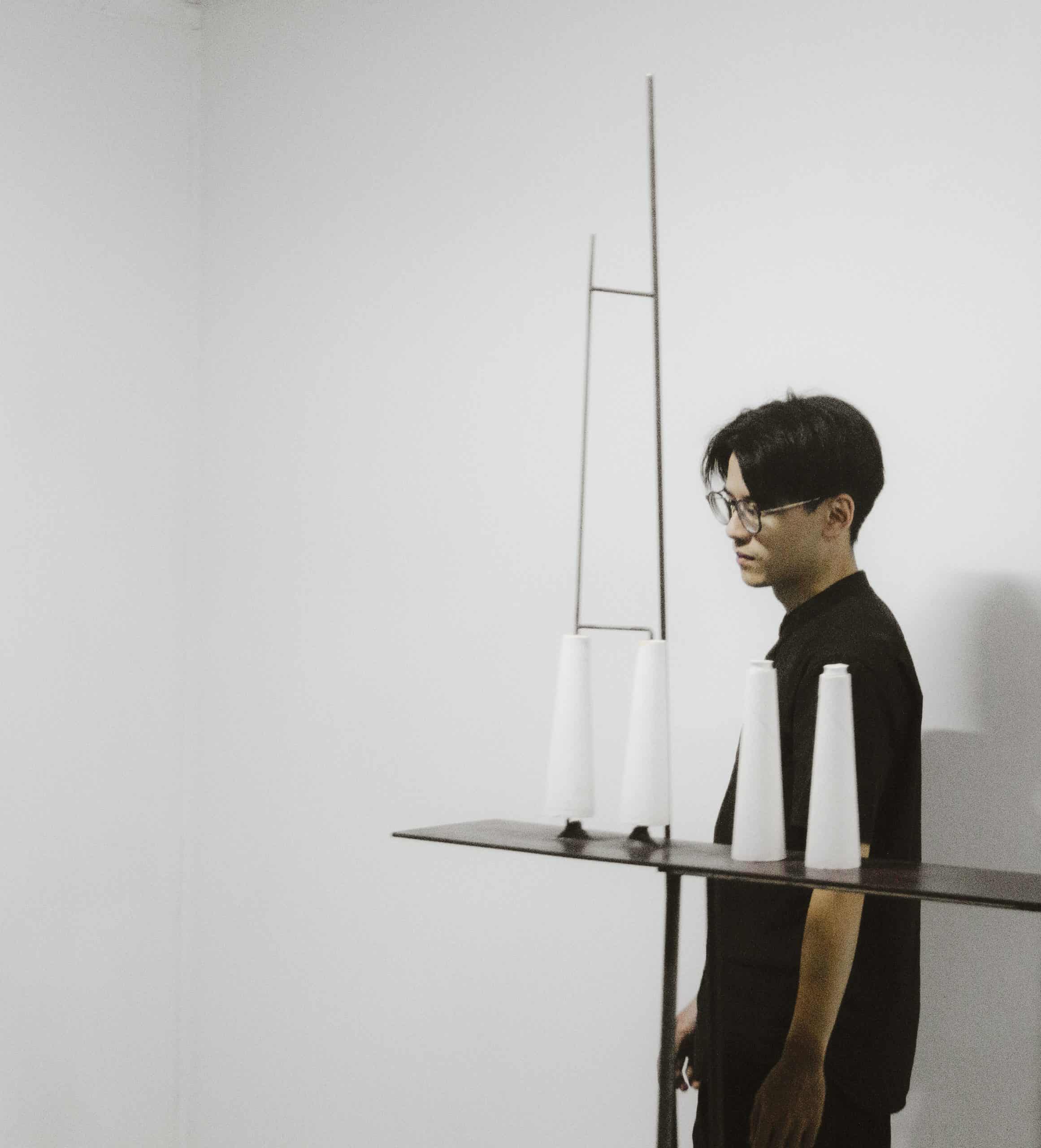

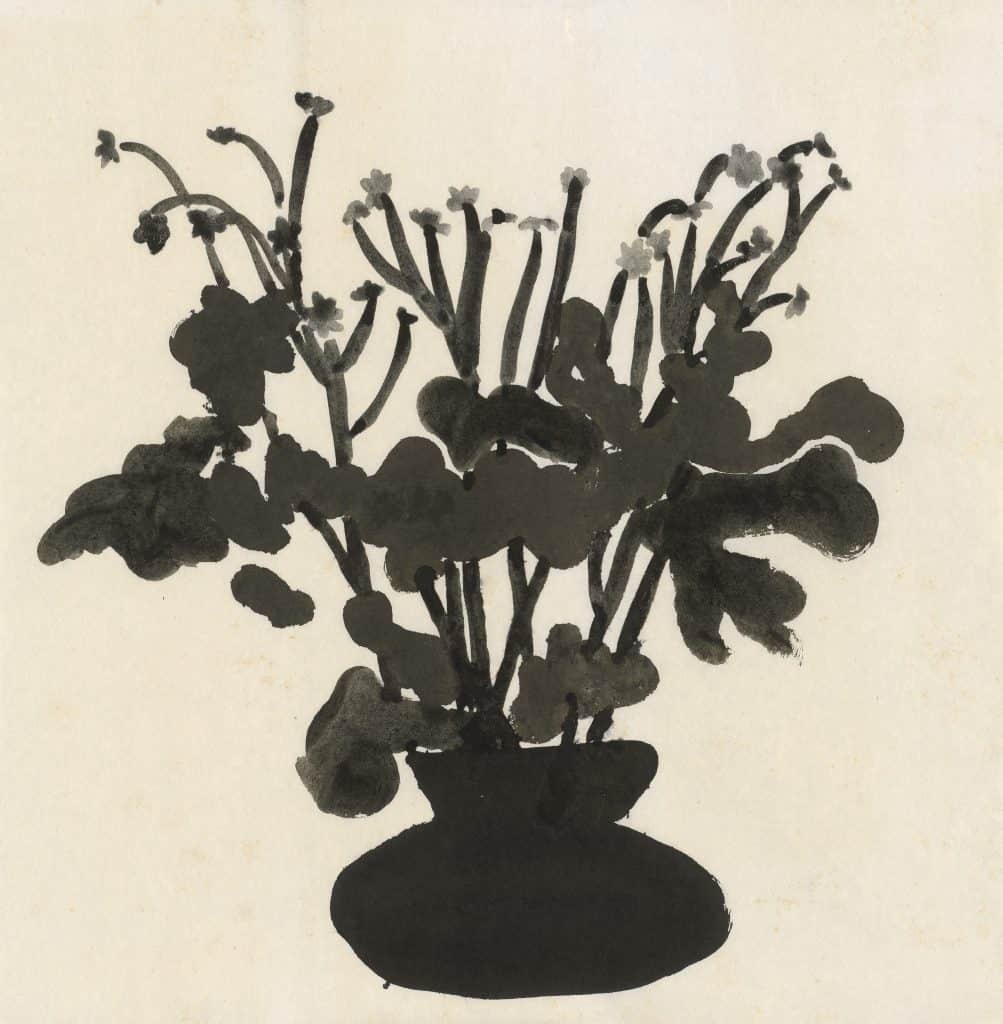

Yu-Ning Yang is good at leaving a grainy, foggy texture and fleeting strokes on raw Xuan paper which is sensitive with old ink. The lightly, translucent, and layered brushstrokes resemble the development process of developing a negative. Ai Makita takes the plastic and metal components in urban landscape and build objects like vital tissues with them. She suggests the question about the boundary between artificial objects and natural objects. The sculpture works of Liang-Cherng Chiow remind people of bent metal construction materials or die-cut cast iron sheets. Chiow attempts to build open venues on alienated landform using pottery clay. Yu-Ning Yang, Ai Makita and Liang-Cherng Chiow all point to the external side of media, making planar objects resonate in differences.

Fan-Hsuan Hsu depicts ocean scenery on Kochi hemp-paper with mineral pigments. The foams of waves on the surface of the shimmering waves are interspersed with starry lights, reflecting the sky that has been deformed because of swaying waves. Sheng-Hung Shiu starts from his personal landscape experience and digital memories and rearrange the photos shot during mountain hiking, creating the dialectical scene between visual information and painting thoughts. Zung-Lung Tsai adopts glazed pottery clay to keep the hard-edge creases and bulging volume after the paper is crumpled into a ball, making smooth and flat surfaces collapse or rise into bent objects. Fan-Hsuan Hsu, Sheng-Hung Shiu and Zung-Lung Tsai all focus on the space and the sensible folds formed by the plane under the effect of force.

Ping-Yi Li embarks on a journey of discovery of her native land and inner self in the aftermath of the epidemic. She places woodcuts and wood plates together, creating a mirror image scenery with a dialogic nature. Jessica Tao places the images of animals in the consumption landscape of contemporary daily life. In the quiet and elegant atmosphere of her works, there is an implied sense of absurdity and dissonance. Mariko Kobayashi adopts weaving, dyeing, weaving, embroidery, and other fiber art techniques combined with multiple materials to portray various kinds of living beings, which embodies a certain cycle of life. Ping-Yi Li, Jessica Tao and Mariko Kobayashi all attempt to have a conversation with other living beings in the environment through their works.

Shintaro Miyake creates a variety of brightly colored, lovable, and dreamy characters on paper that describe his social observations. Atsuko Yamashita continues to depict her inner fantasy world on washi paper, and her iconic images are spread out like a blur of imagination in thin and translucent colors. Yu-Tung Lin uses woods to carve out a variety of closely interconnected yet torn figures of two people connected to each other, which is to investigate the possibilities of love and the intimate emotional relationships between people. Shintaro Miyake, Atsuko Yamashita and Yu-Tung Lin all try to investigate all kinds of splits between selves and in interpersonal relationships.

We can see some themes commonly focused by the contemporary artists both in Taiwan and Japan form the works of the fifteen artists. In terms of dealing with the change and flow of space, Yong-Ning Tzeng focuses on expansion, and Zung-Lung Tsai focuses on folds. When it comes to scenery, Ya-Ting Kao and Sheng-Hung Shiu focus on how digital images and landscape experiences are mixed in memories. Fan-Hsuan Hsu and Ping-Yi Li focus on how can mirror image scenery like water reflection refract individual inner consciousness. Although the work of Yu-Ning Yang exhibited this time is themed on flower, she still attempts to have a conversation with the vision through painting. About the focus on the metal objects in urban experiences, Ai Makita adopts mechanical components in her work, while Jui-Chien Hsu and Liang-Cherng Chiow care about construction materials more. Both Mariko Kobayashi and Jessica Tao use the images of animals in their works. Kobayashi’s work shows the thinking on the relationship between human beings and environment, while Tao’s work responds to the tradition of satirical drawing. Atsuko Yamashita, Yu-Tung Lin and Shintaro Miyake all uses deformed human images to express inclined inner worlds. However, in this case, Atsuko Yamashita is facing herself, Yu-Tung Lin is facing others, and Shintaro Miyake is facing the society.

“Almost the Same Everywhere” is the opening exhibition of “San Gallery.” Susan, the owner of the gallery, is the third child in her family. Because she has used the name “Susan” since she joined the art gallery industry 33 years ago, she then decided to name the new gallery established in 2021 with the word “San (弎)”. On Susan’s last birthday, one of her friends asked a calligrapher to write a calligraphy work with the characters of “Almost the Same Everywhere (前三三,後三三)” and send it to Susan as the birthday present. Susan thought the sentence fit the situation well, so she used it as the name of the opening exhibition. Taiwan is surrounded by the ocean, and Susan considered that it means Taiwan is full of possibilities. Therefore, she expects that the artists of different generations can work together and create the contemporary appearance of arts in Taiwan. She also hopes that San Gallery can provide the space for domestic and foreign artists to exchange and talk with each other and can recommend Taiwanese art works of different generations to Taiwanese collectors of different generations at the same time.

- All

- 高雅婷

- 陶羽潔

- 楊寓寧

- 曾雍甯

- 許聖泓

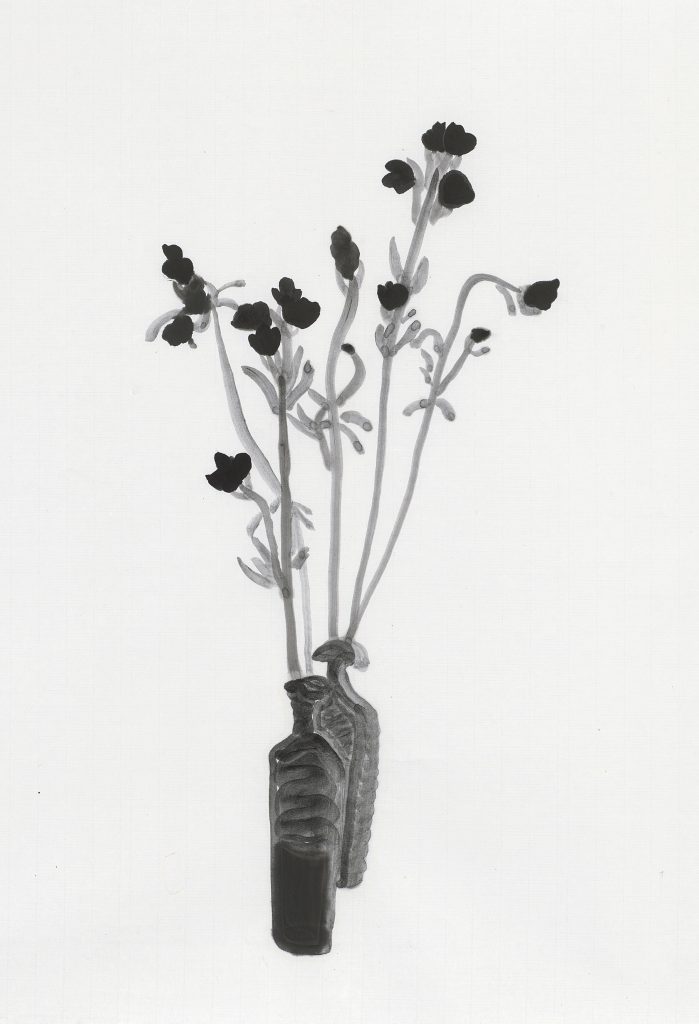

- 徐瑞謙

- 徐凡軒

- 邱梁城

- Ai Makita

- 林禹彤

- 李屏宜

- Atsuko Yamashita

- Mariko Kobayashi

- Miyake Shintaro

蔡宗隆_向光2105_43x33x39cm_陶_2021

蔡宗隆_風景2201_34x35x32cm_陶_2022

楊寓寧_洋甘菊_60X61cm_墨水紙本_2021

楊寓寧_,聖像_69X76cm_墨水紙本_2021

楊寓寧_瓶花_75X50cm_墨水紙本_2021

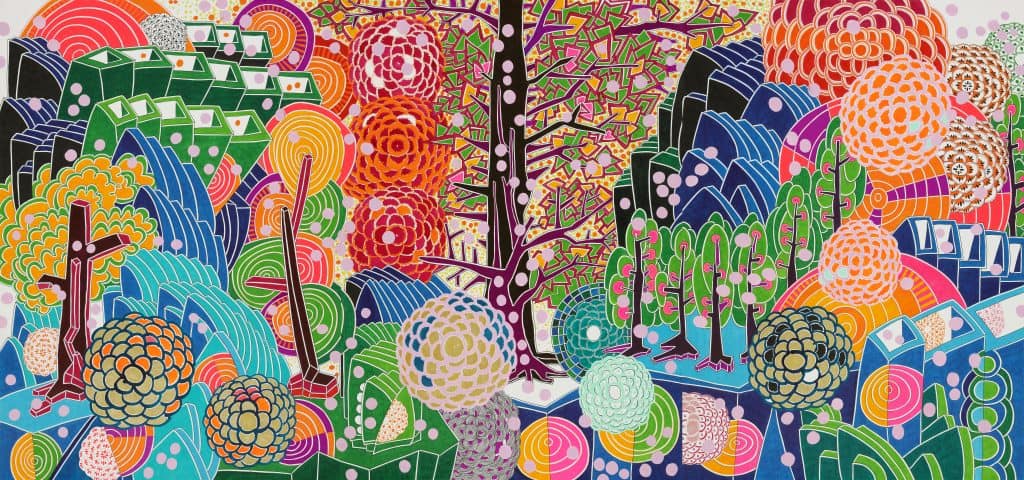

_嶢嶢-22_107x225cm_原子筆、墨水、紙_2021-2022

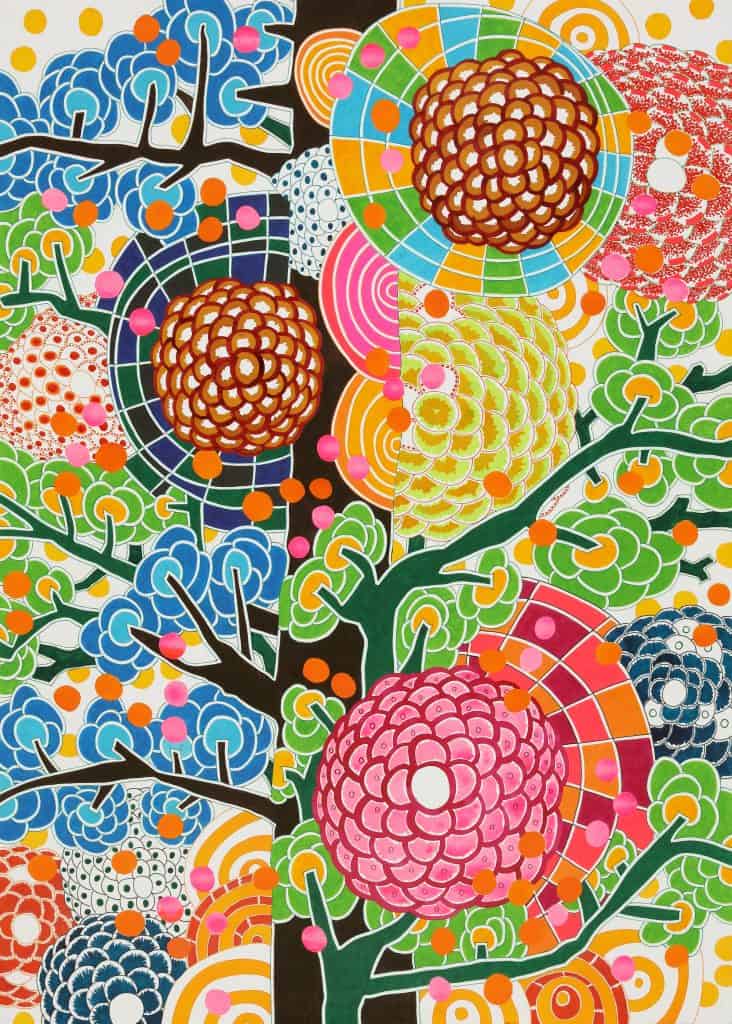

_樹語花9_107x75cm_原子筆、墨水、紙_2021-2022

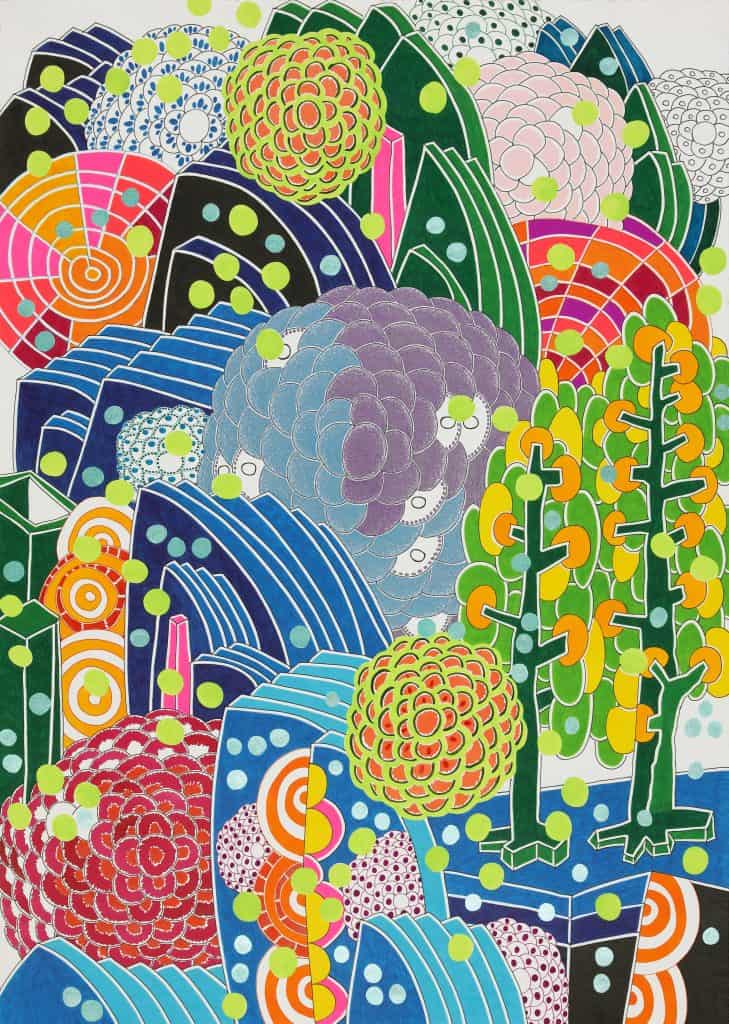

_嶢嶢-24_107x75cm_原子筆、墨水、紙_2021-2022

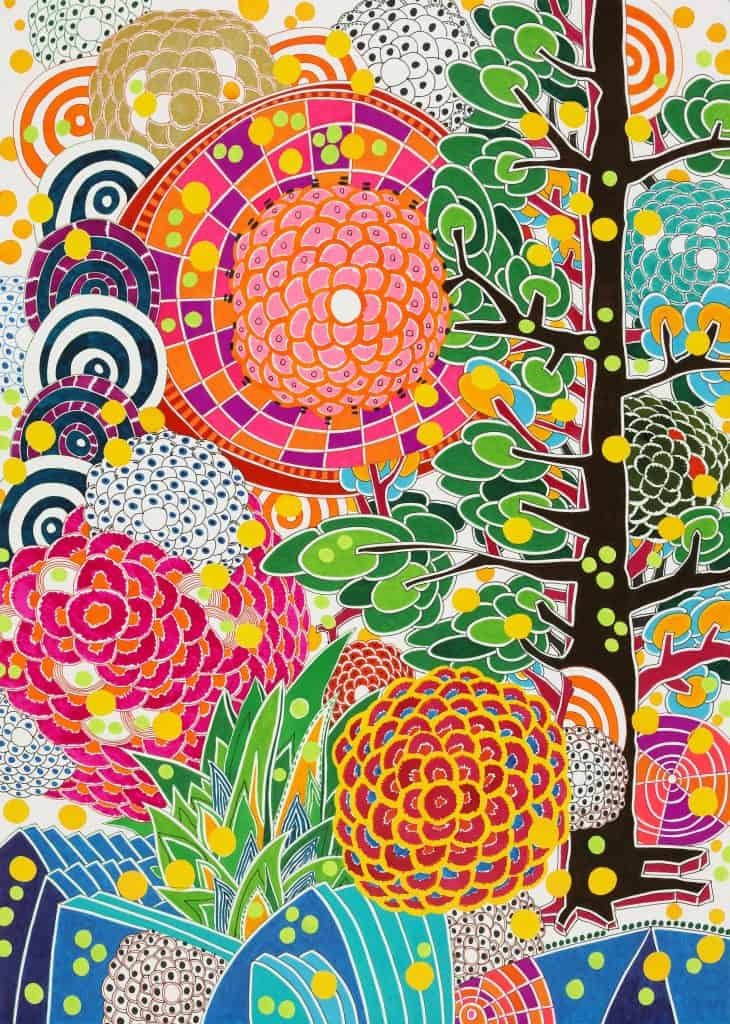

_嶢嶢-23_107x75cm_原子筆、墨水、紙_2021-2022

陶羽潔_夢境_50x50_複合媒材_2021

陶羽潔_無眠_98x74_複合媒材_2021

_觀_37x40.5_複合媒材_2021

_森林32_壓克力顏料、畫布_100x150cm_2022

許聖泓_某日的記憶_壓克力顏料、畫布_80x150cm_2019

許聖泓_向陽_壓克力顏料、畫布_70x100cm_2021

高雅婷_複景素描_黑_複寫紙、法國水彩紙_78.5x109cm_2020.jpg

高雅婷_複景素描_紅_複寫紙、法國水彩紙_78.5x109cm_2020

高雅婷_複景素描_藍_複寫紙、法國水彩紙_78.5x109cm_2020.jpg

_9x7_208-x-52-x-100cm_水泥、鐵、磁磚、聚氨酯_2020

_折角_不銹鋼、聚氨酯_160x130x10cm_2020

_粼粼_116.5x80cm_岩繪具、高知麻紙_2021

Oracle F4. 2021

彼岸。此岸 coast to coast

_時之煉金術-005_陶_H97x88x43cm_2020

_如光漫漫018_陶_H88x145x35cm_2021

_surface≒_91.4×114.3cm_油畫顏料、畫布_2016

林禹彤_黏-10_檜木_6x65x35cm_2021

林禹彤_依-3_樟木_31x21x48cm_2021

林禹彤_依-4_樟木_21.5×36.5×53.5cm_2022

李屏宜_Breathe-Wave-海_三夾板、油墨、Fabriano版畫紙_60x180cm_2020

李屏宜_Breathe-Wave-山_三夾板、油墨、Fabriano版畫紙_60x180cm_2020

_昔日_91x72.7cm_和紙、礦物顏料、水彩、鉛筆、色鉛筆_2021

山下宏子_昔日_72.2×60.6cm_和紙、礦物顏料、水彩、鉛筆、色鉛筆_2021.jpg

山下宏子_昔日_53x45.5cm_和紙、礦物顏料、水彩、鉛筆、色鉛筆_2021.jpg

_Creation_棉、亞麻布、羊毛、矽藻土、黏土_30x30cm_2020-1

小林萬里子_Tanuinu_黏土、土壤、矽藻土、棉、壓克力顏料_9x19.5x19cm_2021.jpg(2)

_Kurobe_黏土、土壤、矽藻土、棉、壓克力顏料_9x19.5x19cm_2021-1

_imagination_棉、亞麻布、羊毛、矽藻土、黏土_30x30cm_2020-1

三宅信太郎_HWACKAMOLE_25.6×50.6cm_鉛筆、色鉛筆、壓克力顏料、麥克筆、紙_2020

ROBOT_33.1-x-31cm-鉛筆、色鉛筆、丙烯酸纖維、壓克力顏料、麥克筆_2020-1

三宅信太郎_PARKING_36.1×31.5cm_鉛筆、色鉛筆、壓克力顏料、紙_2020.jpg

_Melting-poin_135×135cm_油畫顏料、畫布_2022

林禹彤_Whisper-1_樟木_20x39x51cm_2020

林禹彤_Whisper-2_樟木_32.5×42.5x50cm_2020

_The-sun-rises-the-light-breaks_棉_120x150cm_2021-1

李屏宜_那一年。南方以南-海_三夾板、油墨、Fabriano版畫紙_60x180cm_2022.jpg

_ㄧ號樣本_39x27.5_複合媒材_2021

Opening | 2022.02.19 (Sat) 3:00 PM – 6:00 PM

Exhibition Period | 2022.02.19 – 2022.04.02

Location | No. 186, Section 2, Zhongyi Road, West Central District, Tainan City