Yong-Hsu Hsu Solo Exhibition - Boundaries

Boundary– Yunghsu Hsu Solo Exhibition, San Gallery, Tainan, TaiwanExhibition Title: Boundary

Exhibition Dates: 2022/4/23 – 2022/6/30

Opening Tea Reception: 2022/4/23 (Saturday) at 3:00 PM

“Body and Soil as One: On Hsu Yong-hsu’s Solo Exhibition – Boundary”

By: Shen Yu-rong

Written before the exhibition

Writers who engage with artists often resemble trackers in the jungle pursuing wild beasts. The path of the beast forms a labyrinth built by its own movements. If we liken the artist to Daedalus, the master builder of labyrinths, then the writer, along with the viewers, might be seen as Theseus, who attempts to enter, affirm, and delve into (rather than escape) the maze. In this scenario, who plays the role of our Ariadne?

This article seeks possible clues to this enigma through past texts, video records, and artwork. A particular close-up shot appears in the 2015 video “HELiOS Hsiao HiOK: Hsu Yong-xu Solo Exhibition” by Chen Li-Heng Qing, and a similar shot is also featured in Qiu Qin-Ting’s 2019 “Weaving Light with Boundary: The Art World of Hsu Yong-xu.” Both videos coincidentally capture hands with thumbs, forefingers, and middle fingers wrapped and layered with KT Tape, suspended in a “gesture” within the frame. The blue physio tape, undulating around the convoluted lines of the hand, appears to serve as our Ariadne’s thread, guiding us into the labyrinth. These lines not only direct our gaze to a body weary from endless repetition but also focus on the hands that make all movement and traces possible.

Firstly, I want to discuss the complex relationship between these wrapped lines and hands. If Hsu Yong-xu repeatedly presses his fingers into clay, imprinting each moment into the material as a visible trace of depth, an externalized inner writing, then the wrapped tape might be considered a form of writing that begins with an awareness of muscular strain, an internalized external writing. These bright blue lines act like highlights, inviting us to be aware of the writing enabling the artworks during our engagement with them.

In 2006, Hsu Yong-xu introduced his contemplation on “anti-pottery.” He discussed how the materiality of ceramics has always been associated with being “hard yet fragile” in human thought. Thus, he experimented with “large” to challenge the limitations of tools, materials, and techniques and with “thin” to strip away massive structures, directly confronting the material’s physical changes and the dual stress of gravity. In this regard, “hard” and “fragile” refer to “pottery/vessel,” not “clay/earth.” The former is an object isolated from nature by humans, subjugated to usefulness, a negated thing dominated and subdued by a subject. When approached in this manner, the innate connection between humans and nature, or humans and earth, is lost. Therefore, “anti-pottery” is not merely a negation but a negation of the negated; it yearns not for knowledge (savoir) and possession (avoir) but for the restoration of severed continuity.

But does “anti-pottery” mean rejecting all technology and utility, returning to a naive naturalism? Not necessarily. As Bernard Stiegler reflects on the myth of Epimetheus and Prometheus, it is because of Epimetheus’s oversight that humans, unlike other animals, were not endowed with inherent capabilities, necessitating Prometheus to steal technology for humanity to compensate for this deficiency. Technology becomes an innate prosthesis for humans. Humanity’s essence is not naturally predetermined but becomes so through the process of becoming human. The issue is not choosing between technology and nature but how to coordinate both for symbiosis; not only between humans and technological objects but also between the body as a technological object and humans.

Hsu Yong-xu mentioned that during the creative process, apart from a clay cutter, he uses almost no additional tools, relying solely on his hands. But does that mean no other tools exist? Not quite. It’s just that this “tool” conceals itself in handling and is forgotten. Only when the “tool” fails, breaks, and becomes unfit does it become present before the hand. This “tool” is the hand. The human hand acts as a universal tool capable of gripping, twisting, pinching, and molding, linked to the uniquely agile opposable thumb developed through human evolution. Thanks to it, more precise force can be applied to the fingers, enabling the use of objects and other delicate activities.

Thus, on one hand, Hsu Yong-xu’s “anti-pottery” proposes to liberate “pottery/vessel” from the worldly order of utility, while also allowing the handlers of technology a possibility of liberation from utilitarian circuits. On the other hand, Hsu Yong-xu returns the “hand” from purpose-driven movement to questioning itself. The hand not only operates tools but is also a tool perfectly integrated with the flesh (and thus forgotten). The hand’s disengagement from objects allows a temporary pause. What

constitutes this unique technological existence? It’s the “gesture.” The hand can be seen as an ethical technological tool, not only using but also connecting; not only possessing but also caring. Gesture is the silent discourse co-constructed by the hand and the encountered world.

Interestingly, Hsu Yong-xu’s gestures are not constructing an exteriority of vision but responding to an interiority of hearing. The gestures of playing the guzheng over many years (such as the techniques of supporting, splitting, hooking, and picking) explore the realms between string and string, finger and string, finger and sound, sound and meaning. The melody and rhythm built between sounds aim not at confrontation but at harmonious co-construction. “Music” concerns not only the individual’s will but also extends to a perception of existence as a whole; not pointing to the display of skills towards “objects,” but more about a communal existence with “people” at its core. Thus, he must transform himself from a creative subject to a medium.

The hand that marks the intertwining lines does not belong to “one body,” and the clay molded in the hand is not “one medium.” All boundaries are trembling. The environment, mud, humidity, and air pressure are fluctuating, and so are the people within them. From clay forming to drying, experiencing firing, how can giant works maintain their stability without collapsing under the contraction and tension of the clay? It relies not on absolute control but on the perception and prediction of overall external conditions. Clay, body, fire, air are mediums, and so are people. The medium ensures communication, cooperation, and exchange; all boundaries await dissolution, crossing, and then mutual completion. It is at such moments that the body and soil are one.

Bundries

徐永旭_2022-17_高溫陶_高58長60寬57cm_2022b

徐永旭_2022-16_高溫陶_高27長112.5寬52cm_2022a

徐永旭_2022-15_瓷土_高177長105寬45cm_2022a

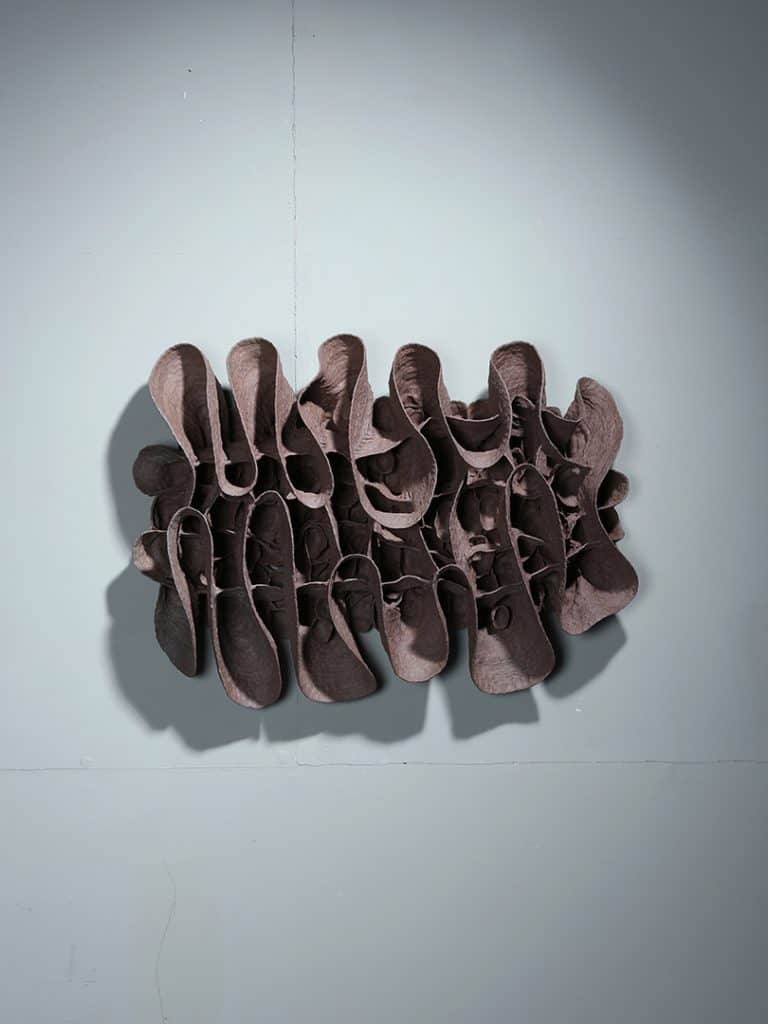

徐永旭_2022-13_高溫陶_高91寬82深21cm_2022a

徐永旭_2022-12 高溫陶_高56寬74深18cm_2022a

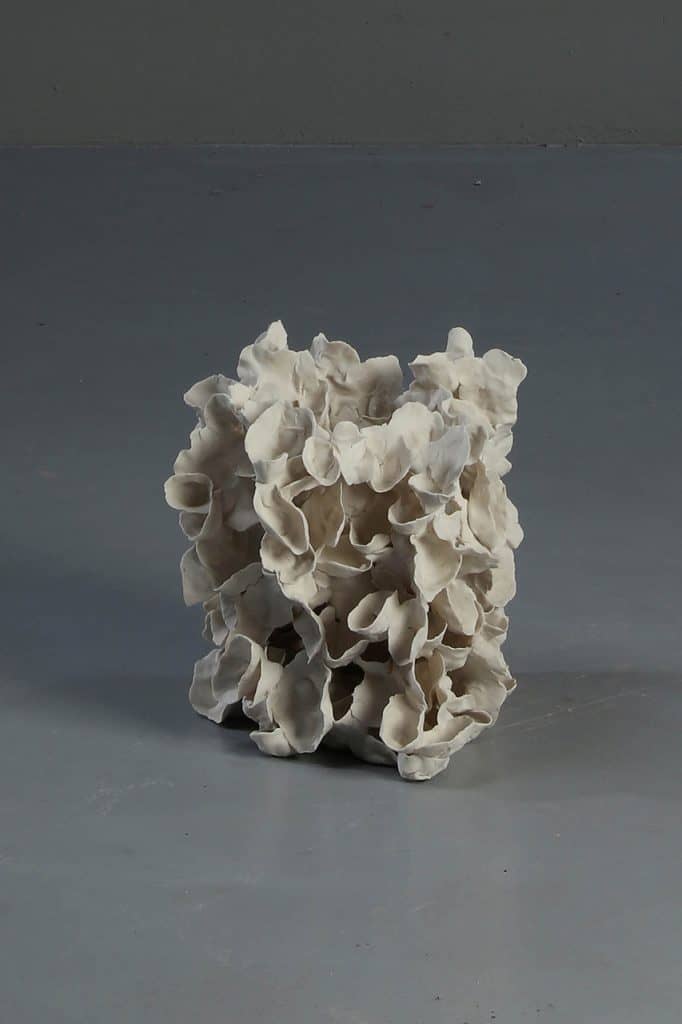

徐永旭_2022-11_瓷土_高72寬70深14cm_2022b

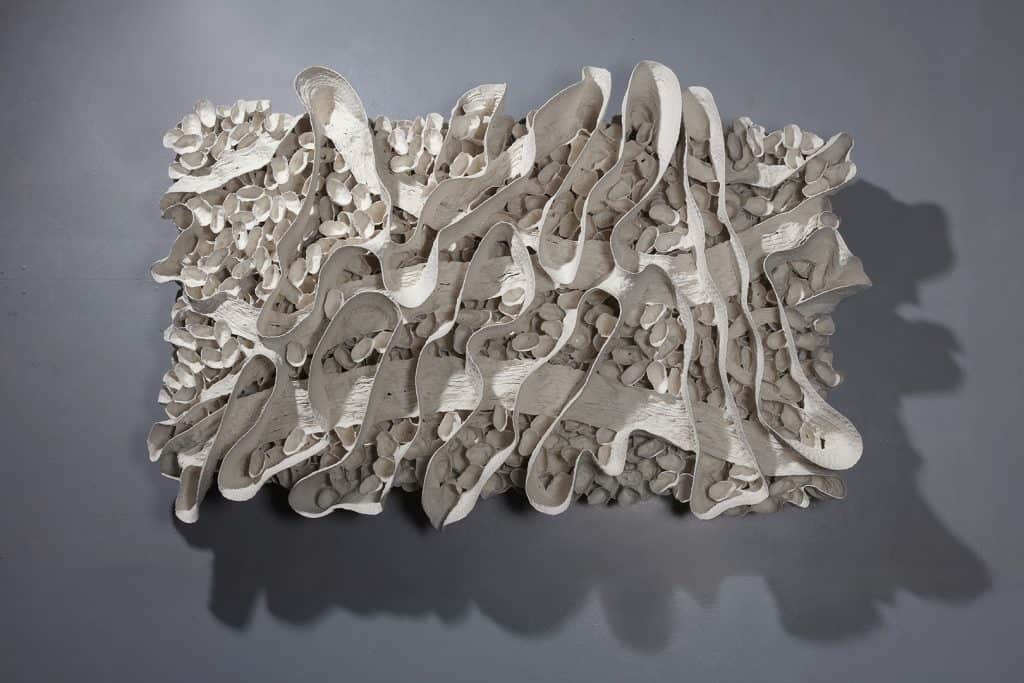

徐永旭_2022-10_瓷土_高31長60寬57cm_2022b

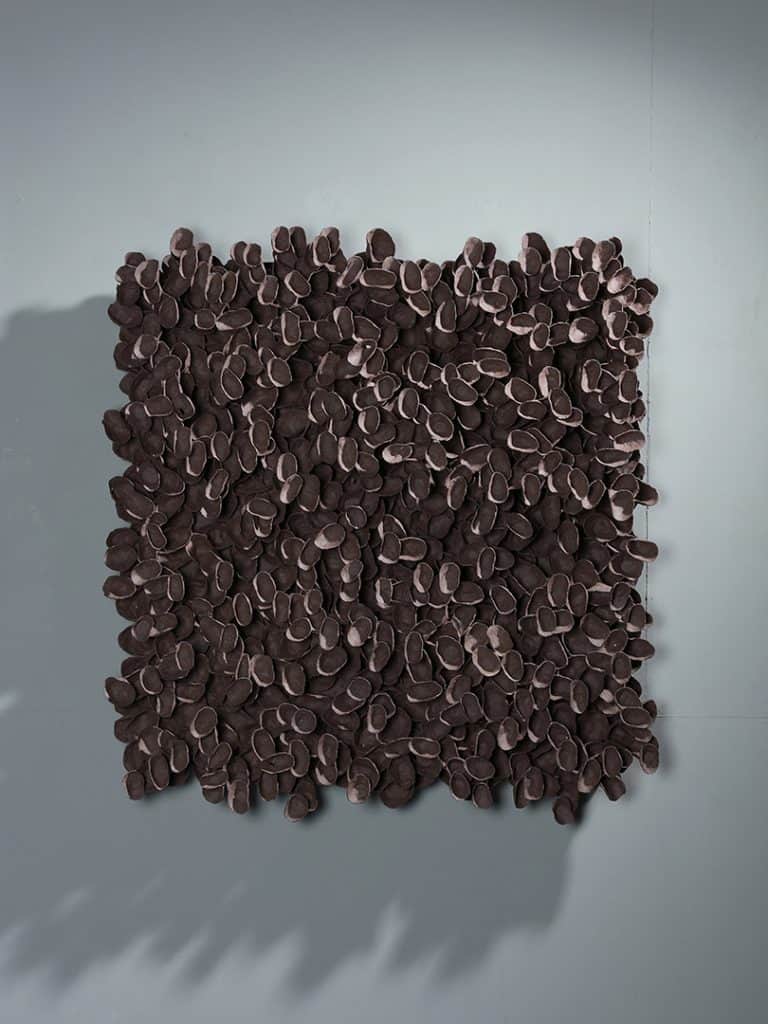

徐永旭_2022-1_瓷土_高116寬175深28cm_2022a

徐永旭_2021-22_高溫陶_高194長160寬130cm_2021b

徐永旭_2020-36_瓷土_高55長64寬57cm_2020

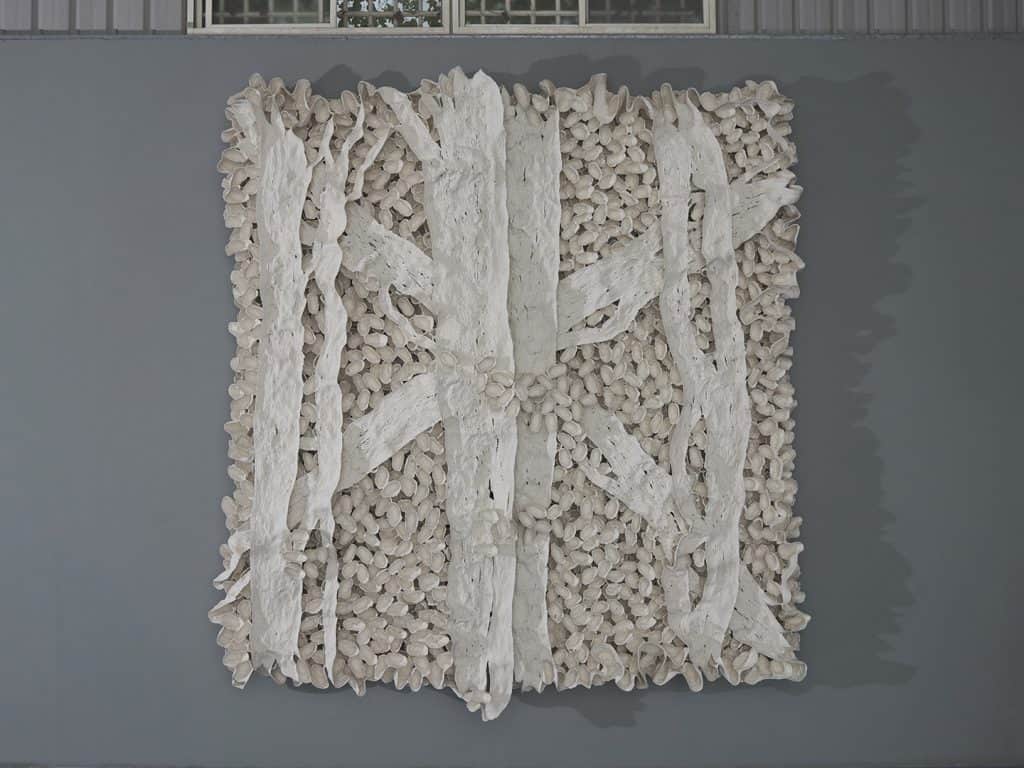

徐永旭_2020-9_瓷土_高302寬287深38cm_2020a

徐永旭_2019-33_高溫陶_高156寬303深33cm_2019b

徐永旭_2022-8_瓷土_高40.5x長27.5x寬24.8cm_2022

徐永旭_2022-7_瓷土_高23x長82x寬40cm_2022(1)

徐永旭_2022-6_瓷土_高70x長38x寬33cm_2022

徐永旭_2022-5_瓷土_高38x長29x寬20cm_2022

徐永旭_2022-3_瓷土_高76.5長49.5x寬44.5cm_2022(1)

徐永旭_2022-2_瓷土_高35.5x長71x寬58cm_2022

徐永旭_2021-26_瓷土_高61.3x長59.5x寬 46.5cm_2021

徐永旭_2021-25_瓷土_高61.5x長44x寬43cm_2021(1)

徐永旭_2020-25_高溫陶_高43x長59x寬 47cm_2020(1)

徐永旭_2019-36_高溫陶_高41x長29x寬23cm_2019