The Animal of Symbols

By Huang Heya

If we say that after the universe’s chaotic beginning, the gods of day and night gave birth to the earth, where plants joyously grew and all things came into being, and creative thought descended upon humanity, then it was humanity that created symbols and learned language.

The German anthropologist Ernst Alfred Cassirer (1874—1945) once stated in “An Essay On Man”: “Man is an animal of symbols.” Humans are the animals that “create” symbols, and it is only through the process of “creating symbols” that humans can gain freedom and truly become “human.” Further explaining, what are “symbols”? Symbols comprise “form” and “meaning,” where “form” is perceivable by human senses, like a “traffic light”; and “meaning” is the agreed-upon significance by the users of the symbol, like how a “red” light signals “do not pass.” Critics often use terms like “specific contexts” or “artistic language” in their reviews, which from a linguistic perspective means: artists endow these symbols’ “forms” with “meaning,” transforming them into “symbols,” while viewers wander among these symbols, experiencing the artist’s process of “gaining freedom,” and further “gaining freedom” themselves.

Looking at Hong Yongxin‘s works, the unique mineral pigments and the repeated washing brushwork create a “mottled feel” that gives the animals and plants in the paintings an environment akin to “soil.” They sit still on the canvas, yet give viewers an illusion of “motion,” as if they are vividly alive in the forest and soil. Interestingly, despite the seemingly “rough” pigments and brushwork, the delicate colors and line handling are still emphasized. In the work “Animal Farm,” different animals overlap, and beneath the dark hides, each exhibits its uniqueness. It reminds me of George Orwell’s (1903—1950) novel “Animal Farm,” where the animals begin to think and establish a world of animal self-governance. This artwork seems to also hint at a powerful force hidden beneath the animal hides, as if to break free from the shackles imposed by humans. Moreover, in Hong Yongxin‘s depictions, animals can be divided into “beasts” and “pets,” with a markedly different atmosphere between works like “Ridge of the Mountain,” “Great Long Legs of the Prairie,” and “Grouse,” and others like “Snore Sleep” and “Dark Eyes.” “Ridge of the Mountain” features a golden halo around a bovine, draped with cloth reminiscent of Persian Empire’s detailed paintings, creating a sense of sanctity and magnificence, while “Snore Sleep,” without elaborate lines and colors, surrounds the central cat with a charming and relaxing “glow” pattern. Beyond these technical discussions, upon first seeing these paintings, I think of the artist endowing these animals with “form” and “meaning,” attempting to communicate their language to viewers. It must be noted that considering humans superior to animals because we have a “language symbol system” is a misconception. Animals also have their own “language symbol systems,” as Austrian ethologist Karl Ritter von Frisch (1886—1982) demonstrated with “the language of bees,” consisting of the round dance and the waggle dance. As Hong Yongxin observes animals, she inadvertently becomes an interpreter, creating a unique system of animal symbols for us.

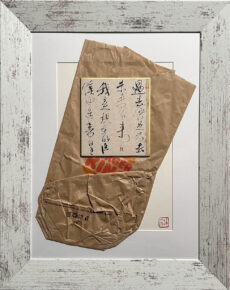

Continuing with the explanation of “form” and “meaning.” Bai Qiaoling’s “form” is quite special, using homemade antique Xuan paper as a base, with ink rendering and red seals adding depth to the painting. I believe the “meaning” lies in her combination of the “gentle and solid” nature of “poetry” with calligraphic skills, presenting a writing that is both soft and strong. The softness of “poetry” can be explained by Mr. Chen Shixiang‘s “Chinese lyrical tradition,” emphasizing that Chinese literature writes about the beauty or regret left under the passage of time, presenting emotions of the moment in a vivid way, and “poetry” is exactly the root of Chinese literature, a characteristic carried on by later literary forms like “Ci” poetry; and Lu Ji‘s concept of “emotional connection with poetry” further illustrates that poets start with “experience” to express inner thoughts. Looking further, Bai Qiaoling shows the “strong” behind the “soft” in her work “As Distance Shows,” adapted from Yan Jidao‘s Ci poem “Youthful Travel—As Distance Shows,” where the character for “water” in “east-west flowing water” is outlined in lighter ink, symbolizing the ending of water-like emotions, and the latter half also alters the original poem’s extreme sorrow of “heartbreak,” ending with “never had such thoughts before,” reducing the lingering sadness for romance, adding a bit of unencumbered spirit. In “Golden Cool Sky Gaze,” extracted from Mr. Lu Xun‘s “Congratulating Christmas in Hong Kong,” the phrase “golden wind brings refreshment, cool dew shocks autumn” is solemnly encapsulated in four characters, especially highlighting the character “refreshing,” which originally means “clear weather, blue” and later developed the meaning “comfortable mood,” where Bai Qiaoling interprets with continuous brushstrokes, using heavy ink and connected strokes to display a bold emotion. I find particularly special the piece “Correspondence—To Wuliwu,” where Professor Shen Yuchang argued in a paper: “When ‘calligraphy’ loses its ‘artistic nature’ due to ‘artification,’ ‘correspondence’ plays a crucial role in helping ‘calligraphy’ regain its ‘artistic nature’ through ‘sincerity.’” Therefore, this piece also possesses a strong ‘sincerity,’ serving as the greatest homage to Tao Yuanming‘s life and character. Bai Qiaoling, inheriting the tradition of Chinese characters, infuses her own “meaning,” thus forming her unique system of special symbols that spans ancient and modern times.

Russian formalist Victor Shklovsky (1893—1984) advocated in “Art as Technique” that “art exists to restore people’s sensation of life, to make people feel things, to reveal the texture of stone.” Thus, the technique in art makes the form difficult, increasing the difficulty of sensation, thereby achieving a “defamiliarization” effect, just as Hong Yongxin’s unique animal symbols let us reperceive the sanctity and adorableness of “animals,” and Bai Qiaoling’s inherited and innovative calligraphic symbols allow viewers to rediscover the emotions behind “calligraphic characters.” Such viewing experiences remind me of Wu Mingyi in “The Land of Bitter Rain,” who said: “In the beginning of ancient times, humans and all things spoke the same language; the song of birds, the light of distant stars, the sound of wind sweeping over the roots of the grass and the waves, and the cries of infants inspired each other…”. Indeed, we are all repeatedly looking at forms to find meaning, deciphering “symbols,” reperceiving “life,” and then learning our language, learning that this is an expression of love, learning how to express love, because in the end, humans are—animals of symbols.

✦ Exhibition Name | The Symbolic Animal – Dual Exhibition of Po Chiao-Ling and Hong Yong-Xin

✦ Artists | Po Chiao-Ling, Hong Yong-Xin

✦ Exhibition Period | 2024/05/18 (Saturday) – 2024/06/29 (Saturday) ✦ Opening Tea Reception and Artist Tour | 2024/05/25 (Saturday) 15:00

✦ Opening Hours | Tuesday to Saturday 13:00-19:00