照看畫面生長的技藝—關於黨若洪個展「Sun Ball—幫助植物生長」

文|沈裕昌

黨若洪在2023年5月6日至6月10日於「弎畫廊」舉辦個展「Sun Ball—幫助植物生長」,展出與植物題材有關的十數件系列新作。「Sun Ball」,根據黨若洪的說法,可以被理解為「陽光作為一個實球」。「陽光」,而非「太陽」,如何被看作「實球」?我們或許可以試著把「陽光」與「實球」的關係,想像為「潛能」及其「實現」。「陽光」不只為視覺所及之萬物賦形,也為萬物提供生長所需之能量。因此,陽光不只在柏拉圖(Plato)「最高善」的意義上,為萬物錘鍛出無限接近理型的理想形式;也在亞里斯多德(Aristotle)「動力因」的意義上,使萬物的形式得以在潛能被實現的過程中不斷蛻變發展。

至於「實球」的意涵,則可見諸米什萊(Michelet)筆下的「鳥」:「鳥幾乎全然是個球體,而牠當然是生命高度凝聚所顯現的崇高、巔峰與神聖狀態。」巴舍拉(Gaston Bachelard)在《空間詩學》中評述道:「對米什萊來說,一隻鳥就是一個充實圓整的球,牠是圓球形的生命。」然而,如果「球」意味著「高度實現的生命整體存在」,那麼對黨若洪來說,「植物」又何嘗不是一個「球」?就此而言,米什萊的「鳥」,與黨若洪的「植物」,或許有著拓撲學意義上的「同胚」(Homeomorphism)關係:從其對於各自生命的高度實現來看,兩者皆可被視作「一個實球」。「陽光」,則是「幫助植物生長」成為「一個實球」,使其「高度實現生命潛能」的能量來源。

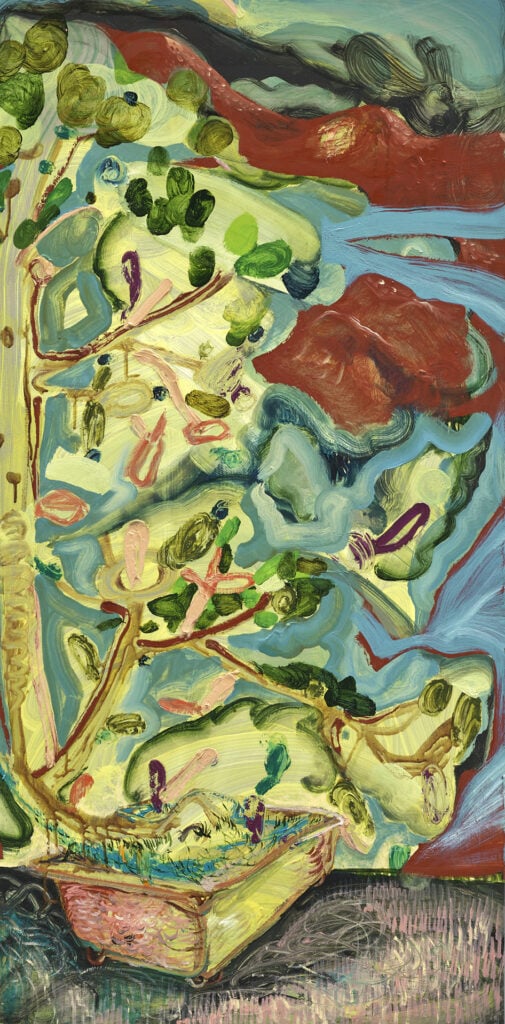

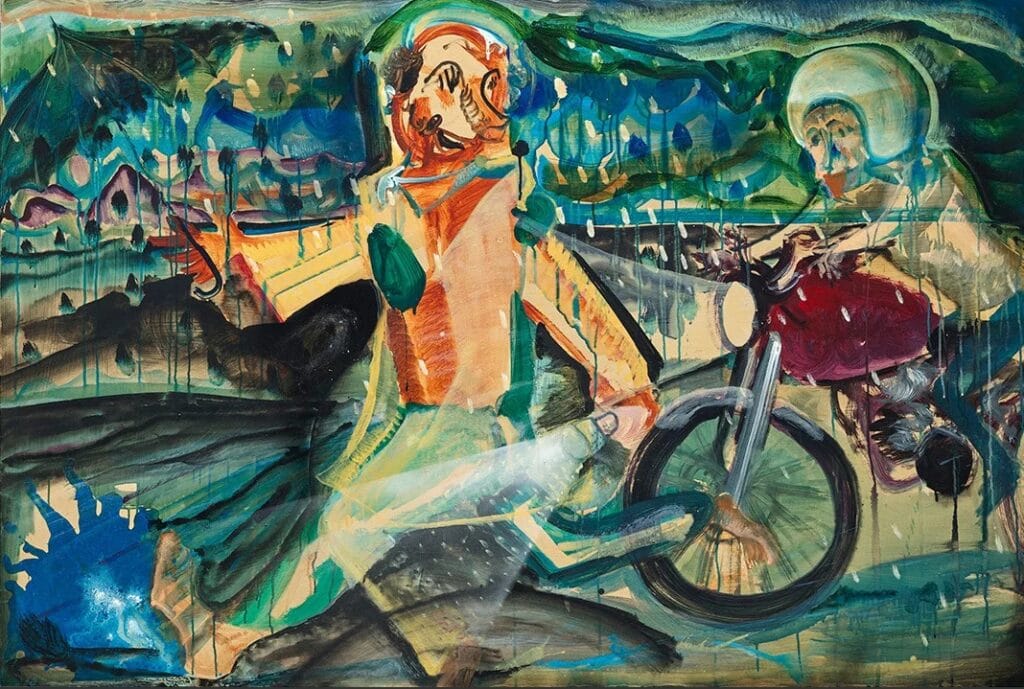

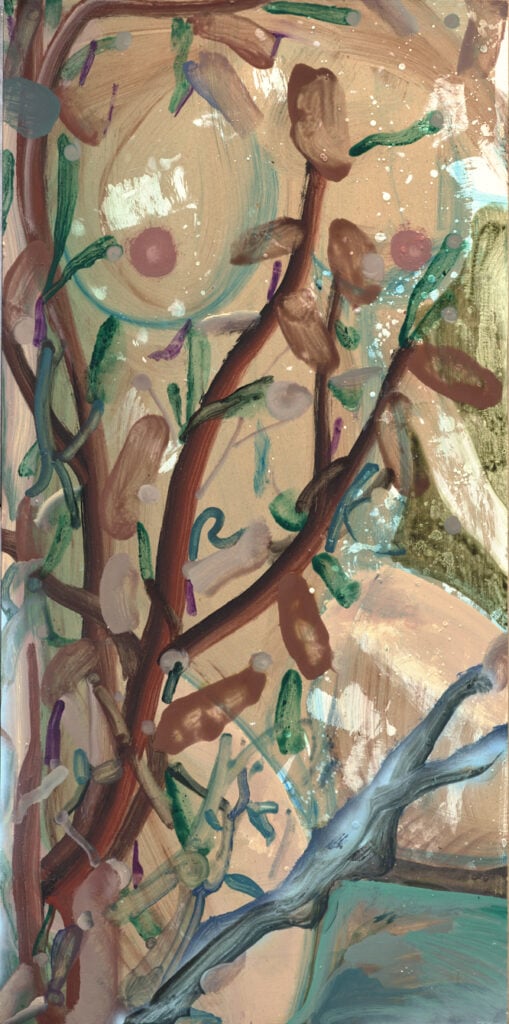

「陽光」與「實球」的關係,也可以被想像為「畫家」與「繪畫」的關係。繪畫並不全然是人為意志的產物。畫家在作畫時,經常能感受到畫面的自生性。但是,畫家也並不只是海德格(Martin Heidegger)所謂「為了作品的產生而在創作中自我消亡的通道」。畫家既不「製作」繪畫,也不是繪畫的「通道」,而是像「幫助植物生長」般,既要加以「照看」,又要「等待」它自行生長。「照看」,不只是「關愛」,還需要具備「生長」的知識。黨若洪在此次展出的植物畫作中所描繪的園藝場景,即有各種協助植物生長的「勾」、「圈」、「條」、「柱」。這些「協助植物生長的輔具」,在黨若洪的畫作中同樣也是「協助繪畫生長的輔具」。「何謂繪畫?」黨若洪在此次個展中的答覆,或即:「照看畫面生長的技藝」。

至於觀者又該如何觀看黨若洪的繪畫?本文認為,黨若洪的繪畫並不依循著特定的「方法」去「製作」,因此似乎不宜將其繪畫,還原為特定的「概念」或「方法」。但本文仍試著提出某種「觀看方式」,並據此提出某些「觀看經驗」。正如7英吋黑膠唱片有所謂的「A-side」與「B-side」,本文也試著將關於黨若洪繪畫的討論,分為「A-side」與「B-side」。在下文中,「A-side」錄製的是關於黨若洪繪畫的「觀看方式」,「B-side」錄製的則是筆者個人的「觀看經驗」。

Nurturing the Skill of Growing Images – On Tung Jo-Hung’s Exhibition “Sun Ball – Helping Plants Grow”

By Shen Yu-Chang

Tung Jo-Hung will hold a solo exhibition entitled “Sun Ball – Helping Plants Grow” at the “San Gallery” from May 6 to June 10, 2023, featuring more than ten series of new works related to plants. According to Tung Jo-Hung, “Sun Ball” can be understood as “sunlight as a solid sphere.” How can “sunlight,” not “sun,” be seen as a “solid sphere”? Perhaps we can try to imagine the relationship between “sunlight” and “solid sphere” as “potential” and its “realization.” Sunlight not only gives shape to everything that can be seen but also provides the energy necessary for everything to grow. Therefore, sunlight not only shapes everything into ideal forms that are closer to the Platonic “highest good” but also allows things to constantly transform and develop through the process of potential realization, as explained by Aristotle’s concept of “dynamis.”

As for the meaning of “solid sphere,” we can see it in Michelet’s description of “birds”: “Birds are almost entirely spherical, and they are naturally a sublime, pinnacle, and sacred state manifested by highly condensed life.” Gaston Bachelard commented in “The Poetics of Space”: “For Michelet, a bird is a fully-rounded ball, it is a spherical life.” However, if “sphere” means “highly realized life as a whole,” then for Tung Jo-Hung, isn’t a “plant” also a “sphere”? In this sense, Michelet’s “bird” and Tung Jo-Hung’s “plant” may have a topological “homeomorphism” relationship: both can be seen as “a solid sphere” from their highly realized life perspective. “Sunlight” helps “plants grow” into “a solid sphere” and provides the energy source for their “highly realized life potential.”

The relationship between “sunlight” and “solid sphere” can also be imagined as the relationship between “painter” and “painting.” Painting is not entirely a product of human will. When painting, artists often feel the self-generating nature of the image. However, the painter is not just a “channel” for creating the painting, nor is he or she “producing” the painting. Like “helping plants grow,” the painter must not only “take care of” the painting but also “wait” for it to grow on its own. “Taking care” not only requires “caring” but also requires knowledge of “growth.” In the plant paintings exhibited by Tung Jo-Hung, there are various “hooks,” “circles,” “lines,” and “pillars” that assist in plant growth. These “tools for assisting plant growth” are also “tools for assisting painting growth” in Tung Jo-Hung’s works. What is “painting”? Tung Jo-Hung’s answer in this exhibition may be “the skill of nurturing the growth of images.”

As for how viewers should look at Tung Jo-Hung’s paintings, this article believes that Tung Jo-Hung’s paintings do not follow specific “methods” to “produce,” so it may not be appropriate to reduce his paintings to specific “concepts” or “methods.” However, this article still tries to propose a certain “way of viewing” and based on it, present some “viewing experiences.” Just as a 7-inch vinyl record has so-called “A-side” and “B-side,” this article also tries to divide the discussion about Tung Jo-Hung’s paintings into “A-side” and “B-side.” In the following text, the “A-side” records the “way of viewing” Tung Jo-Hung’s paintings, while the “B-side” records the author’s personal “viewing experiences.”

關於黨若洪的繪畫(A-side)

我們該如何談論黨若洪及其畫作?畫家與其畫作提供給我們的訊息,就其質與量而言,並不總是相稱。平常,我們觀看畫作;某些時候,我們聽畫家談論其畫作。有時,畫家的言談能為我們解開某些困惑。耳中所聞與眼前所見,在少數時刻,能產生完美的共鳴。然而,在更多時候,儘管所見已經嵌合所聞,在兩者的縫隙中仍然產生出源源不絕的困惑。有些畫家為了消停這種矛盾,選擇說得比畫作少:「讓畫作去說吧!」有些畫家則選擇說得比畫作多:「讓作者去說吧!」最終讓畫作變成教室裡的黑板,或公園裡的肥皂箱。還有些畫家選擇讓畫作說得和自己一樣少:「讓觀者去說吧!」但有另外一些畫家,並不急於消停矛盾,甚至樂於享受矛盾,因此選擇和畫作說得一樣多。黨若洪正是這樣的畫家。

當畫家和畫作說得一樣多,又不急於消停矛盾,最終難免會變成:「讓大家(作者、畫作、觀者)一起說吧!」然而,黨若洪卻不是一位相對主義者和虛無主義者。畫家選擇和畫作說得一樣多,並且樂於享受矛盾,並不意味著邀請觀者任意指稱作品的意涵,反而是在要求觀者領會其看似矛盾的繪畫邏輯。值得注意的是,黨若洪在其訪談中談論的對象,總非作為名詞與結果的「畫作」,而是作為動詞與過程的「繪畫」。儘管如此,我們不能將他的畫作理解為「過程繪畫」,因為他無意把「過程」視為「畫作」。他談論的「繪畫」,仍是一個「物」(object),而不是一件「事」(thing)。只不過,他所談論的,在他筆下作為一個「物」而存在的「繪畫」,既不是他繪製完成的每一件個別作品,也不是這些作品的總和,而是超出這些作品之總和的東西。

說一位畫家的「繪畫」,是超出其「作品」之總和的東西,這樣的談論方式並不必然就導向神秘化。事實上,黨若洪從來無意神秘化其繪畫,他只是不願意輕率地將其繪畫,還原為數個明晰的概念或一套縝密的論述,並因此掩蓋或拭除過程中的各種錯誤或猶豫。因為他清楚地知道,正是過程中的錯誤和猶豫,而非起始處的終極目標和預想路徑,將繪畫導向最後所見到的結果。因此,如果結果值得被肯定,那麼過程中的錯誤和猶豫,肯定比起始處的終極目標和預想路徑更值得被談論。目標當然存在,但是在過程中,卻不可能沒有偏移。有些偏移來自預估與實際的落差,有些則來自靈光乍現的奇遇。畫家在此需要做的,無非就是抉擇與判斷。一連串的抉擇與判斷,構成了一件作品的最終面貌。相比之下,被掩蓋在重重抉擇與判斷之下的原初目標,似乎就顯得不那麼重要了。

就此而言,目標只是過程,過程才是目標。一開始設定的終極目標與預想路徑,是為了使過程得以開展,而不是必然要達到的結果;在過程中與預定目標和預想路徑的不斷偏移,正是並且也導向整個行動最理想的結果。在黨若洪的繪畫中,目標與過程的關係,同樣也是材料、形式、圖像、風格與繪畫的關係。觀看他的畫作,首先看到大量圖像湧現而出,人物、面容、裸體、衣帽、皮靴、瓶罐、水果、盆栽;同時也看到各種筆刷的痕跡,寬幅的塗抹與刮擦、在物象細節與背景空間上飛快掠過的短排線、疊壓在其它圖像上勾勒卻不填彩的輪廓線、混融不同色料拖曳擰轉而過的綿長刷痕、零碎且四散各處的短線條、大小不一的苔點。然而,這些畫面上出現的東西,並非嚴格意義上的圖像,因為它們對於畫家而言並不具備象徵意義,也非透過象徵進行編排組織。但它們也不只是為了提取視覺形式而出現在畫面上的東西,對於畫家而言他們仍存在某些意義。它們的意義,總是少於圖像,卻又多於形式需求。

黨若洪的繪畫過程,更像一局運動賽事,而非一場建地施工。勝負絕非一開始能預見,賽事的節奏也絕不可能跟著計劃進行,所有戰略在開局以後都只能被拋諸腦後,唯有面對當前此刻不斷湧現出的各種問題,應對、解決,不等待但卻又期待某些奇蹟時刻的出現。所謂奇蹟時刻,並不是靈感來臨的時刻,而是進入高度流暢的工作節奏的瞬間。意識到的時候,已經進到節奏裡了。會持續多久並不知道,畫出來的東西好或不好也不知道。只能像奇蹟尚未來臨的時刻一樣繼續畫下去。因此,觀看黨若洪的畫作,並不適合在一開始就駐足靜觀凝視,而應在展場中或急或徐地行走、目光在不同的畫作間或遠或近地打量,直至在畫面中找到令你無法忽視的某一筆,然後循著前後發展,就這麼一直看下去。就像打一場球賽,既不能太緊繃,也不能太放鬆,需要找到某種清警卻靈活的適度緊張感,不要懼怕犯錯,隨時改變戰術。作畫的人如此,觀畫的人也應如此。

Regarding Dang Ruo-hong’s paintings (A-side)

How should we talk about Dang Ruo-hong and his paintings? The information provided by the painter and his works is not always commensurate in terms of quality and quantity. Usually, we look at paintings; sometimes, we listen to painters talk about their paintings. Sometimes, the painter’s words can help us solve some confusion. What we hear and see can sometimes resonate perfectly. However, more often than not, even though what we see and hear has been integrated, there is still an endless stream of confusion in the gap between the two. Some painters choose to speak less than their paintings: “Let the paintings speak for themselves!” Some painters choose to speak more than their paintings: “Let the artist speak!” Ultimately, the paintings become blackboards in the classroom or soapboxes in the park. Some painters choose to let the paintings speak as little as themselves: “Let the viewer speak!” However, there are other painters who are not in a hurry to resolve contradictions, and even enjoy them, so they choose to speak as much as their paintings. Dang Ruo-hong is such a painter.

When the painter speaks as much as the paintings, and is not in a hurry to resolve contradictions, it will inevitably become: “Let everyone (the author, the painting, the viewer) speak together!” However, Dang Ruo-hong is not a relativist or nihilist. The painter’s choice to speak as much as the paintings, and to enjoy the contradictions, does not invite viewers to arbitrarily refer to the meaning of the work, but rather requires viewers to understand his seemingly contradictory painting logic. It is worth noting that in his interviews, Dang Ruo-hong’s subject is not the “painting” as a noun and result, but the “painting” as a verb and process. Nevertheless, we cannot understand his paintings as “process paintings” because he does not intend to regard the “process” as the “painting”. The “painting” he talks about is still an “object”, not a “thing”. However, what he talks about, as a “painting” existing as an “object” in his hands, is not each individual work he has completed, nor the sum of these works, but something beyond the sum of these works.

To speak of a painter’s “painting” as something beyond the sum of its “works” does not necessarily lead to mystification. In fact, Dang Ruo-hong never intended to mystify his painting. He just didn’t want to rashly reduce his painting to several clear concepts or a rigorous discourse, thereby obscuring or erasing the various errors or hesitations in the process. Because he knows clearly that it is the errors and hesitations in the process, rather than the ultimate goal and expected path at the starting point, that lead the painting to the result seen in the end. Therefore, if the result is worthy of affirmation, the errors and hesitations in the process are undoubtedly more worthy of discussion than the ultimate goal and expected path at the starting point. The goal certainly exists, but in the process, it is impossible not to deviate. Some deviations come from the gap between estimation and reality, and some come from the sudden inspiration. What the painter needs to do is nothing more than choosing and judging. A series of choices and judgments constitute the final appearance of a work. In comparison, the original goal hidden under numerous choices and judgments seems less important.

In this sense, the goal is only the process, and the process is the goal. The ultimate goal and expected path set at the beginning are meant to enable the process to unfold, not necessarily to be achieved. The constant deviation from the predetermined goal and expected path during the process is precisely what leads to the most ideal outcome of the entire action. In Dang Ruohong’s paintings, the relationship between the goal and the process is also the relationship between the materials, forms, images, style, and painting. When viewing his works, one can first see a large number of images emerging, including figures, faces, nudes, clothing, hats, boots, bottles, fruit, and potted plants. At the same time, one can also see the traces of various brushes, wide strokes and scratches, short lines that quickly pass over the details of objects and the background space, outlines that are sketched but not filled in on top of other images, long and winding brushstrokes that blend different colors, and scattered short lines and dots of different sizes. However, these things that appear on the picture are not strictly speaking images, because they do not have symbolic significance for the painter, nor are they organized through symbolism. But they are not just things that appear on the picture for the sake of extracting visual forms. They still have some meaning for the painter. Their meaning is always less than that of the images but more than the requirements of the forms.

Dang Ruohong’s painting process is more like a sports game than a construction site. The outcome cannot be foreseen at the beginning, and the pace of the game cannot follow the plan. All strategies can only be abandoned after the start, and only by facing various problems that constantly emerge at the moment and dealing with them can we hope for some miraculous moment to appear. The so-called miraculous moment is not the moment when inspiration comes, but the moment when we enter a highly fluent working rhythm. When we realize it, we have already entered the rhythm. We don’t know how long it will last, and we don’t know whether what we draw is good or bad. We can only keep drawing like waiting for a moment of miracle. Therefore, when viewing Dang Ruohong’s works, it is not suitable to stop and gaze at them at the beginning. We should walk around the exhibition hall quickly or slowly, look at the paintings from different distances, and find a stroke that cannot be ignored in the picture, then follow the development before and after and continue to look. Just like playing a game, we cannot be too tight or too relaxed. We need to find a kind of clear and alert but flexible and appropriate tension and not be afraid of making mistakes and changing tactics at any time. The person who paints should be like this, and the person who views the painting should also be like this.

關於黨若洪的繪畫(B-side)

總是從隨意地投擲顏料到畫布上開始。比起塗鴉,更像為了讓意識聚焦而信手抄起某個物件,把玩,擺弄。綜合性的揉塑,指掌自動導航。在土塊之上重複添加土塊,複合之物在做功中質變成為有機之體,生命彷彿湧現其中。被賦予記憶的物質,似乎擁有自我意識,裹挾著手引它前行。視覺不再作為觸覺的前導,觸覺能預觸它期待的所觸。不是投球,而是運球。信任球從地向手的必然回饋,掌握聽覺的方向盤。篤定,往復。然後是地表的問題。纖維板表面光滑,吸收性高。表面光滑,不像畫布特有的陣列的顆粒感,筆刷滑過織品表面就沙沙作響,筆具向下施力就如在厚實的地毯上拖沓而行,力量被沙坑般抵消然後陷落。吸收性高,不像木板有特定的紋理走向,儘管筆走其上輕快而堅實,疏水性卻過高,油料未乾時如行車過水坑,筆具含顏料量過高就怕失速打滑。纖維板上的筆痕,像在楓木地板上運球時清脆明快如鼓聲的回音。

有時,下層油料未乾而筆痕尚在。用上另外一種顏色,為了引出新的刷痕。色調在刷具的拖曳中混融變化,但不會特別被注意,因為目光已被交疊的刷痕所吸引。深的純色刷過淺而未乾的粉色,溢出筆具兩端的深色顏料化成雙鉤墨線,淺粉色被包夾在內,如肉塊賦形而生。停頓,轉折,腕肘反向施力,撒手而過,裂變成閃電,神經或是樹杈。淺的粉色刷過深而未乾的純色,厚實得像沒有任何光線或聲響可以穿透的團塊。形象消失於其中,返回如底色般有待被重新揉塑的混沌狀態。但不再是基質,而是特定的團塊狀的物形。軀幹、手臂、果實,或者瓶口吞吐出的燃煤煙般的蒸氣霧,總之球體及其同胚。深的純色刷過淺而乾透的粉色,重新勾勒,透出乾淨明晰的底色。尤其深綠或者深藍,隔著染色玻璃杯瓶窺看室內人物靜物變形。淺的粉色刷過深而乾透的純色,霧化,逆光賦形。或是削弱下層對比,重新定色,或是乾脆全面覆蓋。透明的深純色是加法的雕,不透明的淺粉色是減法的塑。

或許塊面只是臆想,從來不曾在筆具下現身。畫面上存在的,只不過是粗細不同的線段。粗線段覆蓋在細線段之上,底下必定有所透出。或是選擇透明度高的顏色,或是乾筆拂掠而過,或是下層未乾時輕抹過,或是噴漆,或是乾脆細碎地點滿它。否則就只是遮蓋。寧願留下混濁色塊邊緣鮮亮的不透明粉色輪廓,也好過只是單純地遮蓋。細線段覆蓋在粗線段之上,進一步塑形。最常見的情況:短排線與小碎點。同一流向,或四散輻射。短排線不意味著陰影,也不見得暗示量體,更像某種重點提示,閱讀時的畫記眉批。囚室牆上計日,或無意識地重複羅列,有時變成電話線般纏捲虯結,緊密壓縮後築構成一道看似有向量的側面。小碎點,有密亦有疏。密時如橡膠板上金屬雕刀刮鑿過,帶有橡膠彈性與抗性的凹槽,用力挖鑿入畫面的筆痕,中間透而兩邊濃稠。疏時如刮過數日後長出的稀疏毛根,星羅棋布,壁畫或童畫式的葉點,流理台上的茶葉渣,圖像性的雨點。

不時地有人物出現。面容疊加著面容,四分之三正側像的左臉,右撇子塗鴉的習慣。繼而是對視的面容。從額頭到鼻尖,最核心的垂直結構。雙眼,有時則是巨大的坑窪。茫然低眉凝望,或是與觀者對視的空洞目光。透出底下的混沌無序,或是點上瞳孔,用視線來替代意義。張嘴,露齒或是鼓腮,吹氣或是嚎叫或是吞食,標誌著方向的出入,口水或是聲音。從手背到指尖,最核心的水平結構。因為有所持拿:花卉,果實,灑水壺,園藝鏟。也有麥克風。體面的衣著:領子與靴子,銳角與圓弧,扣子與繫帶,垂直排序,斷裂的點列,或者交叉的連結。值得記住的面容,或剛好瞥見的靜物組合,同樣的形式,球與柱的堆疊。即便是平凡的時刻,也要戲劇性地會面,才能深刻記得。把經驗轉錄為視覺的唱盤,任何微小的刮擦痕跡,都可以透過放大器,產生令人驚駭的爆音,或華麗的跳針。

On Dang Ronghong’s Painting (B-side)

It always starts with casually throwing paint onto the canvas. Rather than graffiti, it’s more like picking up an object to focus the consciousness, playing with it, and manipulating it. The comprehensive molding is directed by the fingers. Repeatedly adding soil to the block, the composite material undergoes a qualitative change and becomes an organic entity in the process, as if life is emerging from it. The material that is endowed with memory seems to have self-awareness, carrying the artist’s hand as it moves forward. Visuals are no longer the forerunner of touch; touch can anticipate what it expects to touch. It’s not throwing the ball, but dribbling. Trusting the inevitable feedback from the ball to the hand, the steering wheel is controlled by the hearing. Firm and back and forth. Then comes the problem of the surface. The fiberboard surface is smooth and absorbent. The surface is smooth, unlike the grainy feeling unique to canvas. The brush rustles across the fabric’s surface, while the brush pushes down as if walking on thick carpet, and the force is counteracted by sandpit-like resistance and then falls. The absorbency is high, unlike wood with a specific grain direction. Even though the brush moves lightly and solidly on it, the hydrophobicity is too high, and when the oil paint is not dry, it feels like driving through puddles, and the brush is afraid of losing speed and slipping. The brush marks on the fiberboard are like the clear and crisp echoes of dribbling on maple wood floors.

Sometimes, the underlying oil paint is not dry, and the brush marks remain. Another color is used to bring out new brush marks. The color tone changes and blends in the brush’s drag, but it is not particularly noticeable because the overlapping brush marks are already captivating. The deep monochrome color brushed over the light, undried pink spills out to become double-hook ink lines at both ends of the brush, and the light pink is sandwiched inside, like a piece of meat taking shape. Pause, turn, reverse the elbow’s force, let go, and split into lightning, nerves or tree branches. The light pink brushed over the deep, undried monochrome color is as thick as a lump that no light or sound can penetrate. The image disappears in it, returning to the chaotic state that needs to be reshaped like the base color. But it’s no longer a substrate; it’s a specific lump-shaped object. The trunk, the arm, the fruit, or the steam and fog spitting out of the bottle’s mouth, in short, the sphere and its same kind. The deep monochrome color brushed over the light, dried pink redraws the outline, revealing a clean and clear base color. Especially deep green or blue, it peeps into the deformation of indoor people and still lifes through the stained glass. The light pink brushed over the deep, dried monochrome color vaporizes and shapes against the light. It either weakens the contrast of the underlying layer, recolors it, or simply covers it all. Transparent deep monochrome color is additive carving, while opaque light pink is subtractive sculpture.

Perhaps the surface is just an illusion that never appears under the brush. What exists on the canvas are only lines of different thicknesses. Thick lines cover thin lines, and something must be revealed underneath. This can be achieved by using a color with high transparency, by brushing over with a dry brush, lightly rubbing over when the underlying layer is not yet dry, spraying paint, or simply dotting it with small strokes. Otherwise, it would just be a cover-up. It is better to leave a bright and opaque, slightly blurred outline of the color block rather than just a simple cover-up. Thin lines are overlaid on thick lines to further shape the image. The most common situation is short lines and small dots. They can be in the same direction or scattered. Short lines do not necessarily mean shadows or imply volume. They are more like key hints or annotations when reading the image. They can resemble markings on a prison wall counting the days or unconsciously repeating lists, sometimes becoming twisted and tightly compressed into what appears to be a vector side. Small dots can be dense or sparse. When dense, they are like grooves created by a metal knife scraping over a rubber plate, with the rubber’s elasticity and resistance, digging deeply into the brush marks in the picture and with the center being translucent and the sides thick. When sparse, they are like sparse hairs that grow after several days, with leaf spots in a mural or childish drawings, tea leaves on a draining board, or pictorial raindrops.

Characters appear from time to time. Faces overlap with faces, left profiles with three-quarters of a right squinting face. Then there are faces staring at each other. The most essential vertical structure from the forehead to the nose. The eyes, sometimes with huge hollows. Gazing low with a blank stare, or empty eyes gazing at the viewer, revealing the chaos and disorder below or dotting the pupils to replace meaning with gaze. Mouth open, teeth exposed, puffed cheeks, blowing air or screaming or swallowing, indicating the direction of entry or exit, saliva or sound. The most essential horizontal structure from the back of the hand to the fingertips. It is essential because there is something being held: flowers, fruit, watering cans, garden shovels. There is also a microphone. There are dignified clothes: collars and boots, sharp angles and arcs, buttons and ties, vertical order, broken points, or cross-linking. Faces worth remembering or still-life combinations glimpsed are of the same form, stacked balls and pillars. Even in ordinary moments, dramatic encounters are necessary to remember deeply. The experience is transcribed into a visual record player, and any tiny scratch marks can produce shocking explosions or gorgeous skips when amplified.

展名 | 黨若洪個展「Sun Ball—幫助植物生長」

參展藝術家 | 黨若洪

展覽 | 2023.5.6(六)~6.10(六)

開幕茶會 | 2022.5.6(六) 15:00-16:00 講座 16:00-18:00 開幕