Hsu Yung-hsu's Solo Exhibition - Boundary

Name:Boundary

Period:2022/4/23 – 6/11

Opening:2022/4/23(Sat) PM 3:00

Body and Earth: “Hsu Yung-hsu’s Solo Exhibition – Boundary”

By Shen, Yu-Rung, before the opening

A writer dealing with an artist is very much like a stalker in the jungle chasing a beast. The path taken by the creature forms a labyrinth of its own making. If the artist is likened to Daedalus, the superb builder of the labyrinth, then perhaps the writer who joins the viewer is Theseus, who ventures into the maze, affirms it, and wishes to go deeper into it (rather than escape). In this way, who is our Ariadne?

It is from the examination of these past texts, visual records and works that this article is written to find possible clues to confront this mystery: In the 2015 film entitled “HELiOS HiOK: Hsu Yung-hsu’s Solo Exhibition” by Chen Li Herng-ching, a close-up with a short focal length lens appears, and a similar shot is found in Chiu Chin-ting’s 2019 film entitled “Hsu Yung-hsu: A World Made Light.” The two coincide in capturing a hand with the thumb, forefinger and middle finger wrapped in KT Tape in layers, suspended in a certain “gesture” in the frame. The blue KT Tape (the strips that undulate around the hand), which is intertwined on the surface of the skin, seems to be the thread of Ariadne that leads us into this labyrinth. It directs our attention not only to the exhausted body in this endless repetition, but also to the hand of know-how that makes all actions and traces possible.

First, I would like to point out the complex relationship between these entwined threads and the hands. If Hsu’s repetitive finger pressure imprints each moment, grid by grid, into the clay, making it appear as writing with deep visible marks, an externalized inner writing, then these entwined tape strips might be seen as writing that emerges from an awareness of the strain on the flesh, an internalized external writing. These bright blue threads are like highlights, beckoning us to view the writings (i.e. pieces of works) while being aware of what makes writing possible.

Hsu’s reflection on “anti-ceramics” dates back to 2006. The material of ceramics, he says, has been associated with “hardness and fragility” in the mindset of humankind. As such, he attempts to challenge the limitations of tools, materials and techniques by going “big,” and to remove the large structure by going “thin,” facing up to the physical variations in the material itself and the effects of the double stress of gravity. In this sense, “hard” and “fragile” refer to “pottery/ware” rather than “pottery/clay”: the former only acts as an object, a thing that is isolated from nature and subordinated to usefulness, a negated thing that is dominated and submits to the subject. Once one confronts it in this way, an innate connection between man and nature, or man and earth, is lost. “Anti-ceramics” is therefore not a mere negation, but a re-negation of the negated; it desires no longer to savoir (know) and avoir (possess), but to restore the severed continuity.

But does “anti-ceramics” mean a rejection of all technical and usability values and a return to the naivety of naturalism? No, it is not. As Bernard Stiegler had elucidated the Greek myth of Epimetheus and Prometheus, it was precisely because of Epimetheus’ faults that man was not endowed with the same potential as other animals, so that it was left to Prometheus to make up for such a loss by stealing technology for man. Technology becomes the inborn prosthesis of the human being. And what makes a human being human cannot break away from the need for technology, because a “human” is not what he or she inherently is, but becomes what he or she is in the course of humanization. The question is not the choice between technology and nature, but how to reconcile the two in a symbiosis; a coexistence not only between man and technical objects, but also between the body as a technical object and man.

Hsu Yung-hsu says that he hardly uses any additional tools in the process of creating his work, other than a clay slicer, and relies solely on his own hands. But don’t other tools come into play besides the clay slicer? Well, they do. It is just that the “tool” conceals itself in the zuhandenheit (readiness-to-hand) and is forgotten. It is only when the “tool” fails, when it is damaged, when it does not work that it assumes the vorhandenheit (presence-at-hand). And the “tool” referred to here is – the hand. The human hand is like a versatile tool, and its ability to grip, twist, squeeze and shape things is linked to the evolutionary development of an unusually flexible opposable thumb. Thanks to it, it is possible to apply force to the fingers with greater precision and to engage in precision activities such as the manipulation of objects.

Thus, on the one hand, Hsu proposes the usefulness of detaching “pottery/ware” from the order of the material world through “anti-ceramics,” and on the other, the possibility of liberating the practitioner of the technique from the utilitarian loop. Hsu, meanwhile, shifts the “hand” from purposeful finger motion back to questioning itself. The hand not only operates the instrument, but is also a tool that is perfectly integrated (and thus forgotten) with the physical body. The hand is decoupled from the object, leaving it on hold for the moment. What constitutes this special technical presence? It is the “gesture.” The hand can be seen as a technical tool in terms of ethics; it is not just about use, it is more about connection; it is not just about possession, it is more about care. Gestures are the silent words of the hand and the world it encounters.

Interestingly, Hsu’s gestures do not so much build visual externality as they do respond to auditory interiority. The way we play the guzheng with our fingers (such as the fingering techniques of thumb going in, going out, middle finger going in, going out) is to explore the realm between string and string, string and finger, finger and tone, and tone and meaning. The melody and rhythm built between the tones is not about confrontation, but about harmony. “Music” concerns not only the individual mind, but extends to the feeling of existence as a whole; it is not about the technical expression of “things,” but about the finality of communal existence achieved with the “mankind” at its core. Therefore, he must himself morph into a medium from the subject in artistic creation.

The hand that is wrapped in the marked threads does not belong to a “body,” nor is the clay that is kneaded in the palm “a medium.” All boundaries are swaying. The environment, the soil, the humidity, and the air pressure are volatile, and so are the people in it. From clay making to drying all the way through the firing process, how a giant work of art can maintain its stability without collapsing as the clay shrinks and pulls, hinges not on absolute control but on the perception and prediction of the overall external conditions. Earth, body, fire and air are the mediums, as are humans. The mediums guarantee communication, collaboration and exchange, and all boundaries are waiting to be broken down, crossed and then made whole for each other. It is at such moments that the body and the earth become one and the same.

徐永旭_2022-17_高溫陶_高58長60寬57cm_2022b

徐永旭_2022-16_高溫陶_高27長112.5寬52cm_2022a

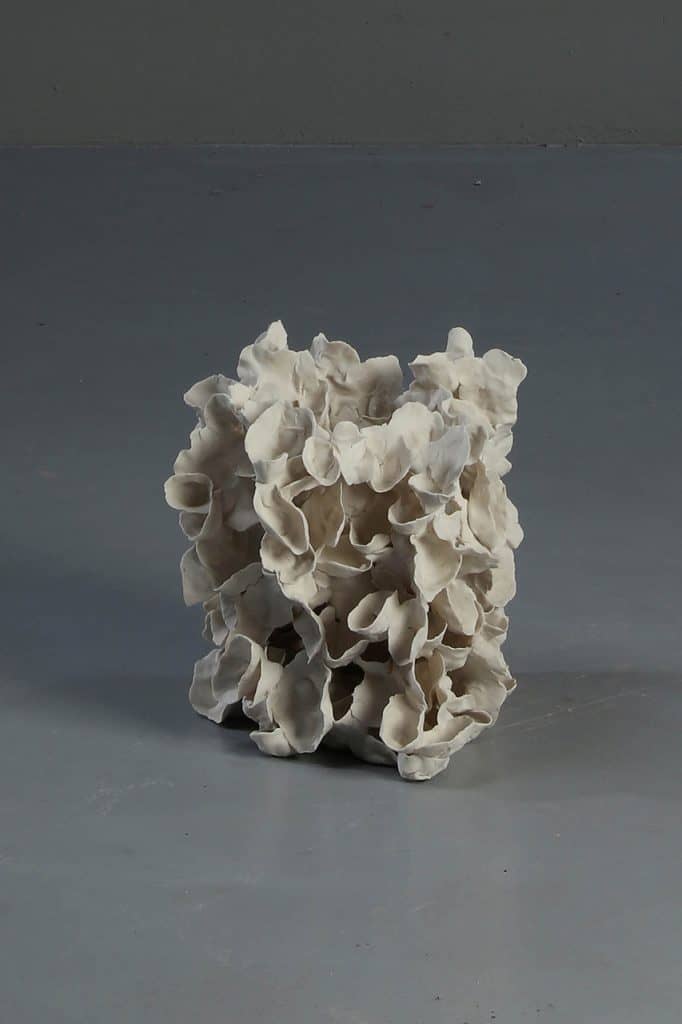

徐永旭_2022-15_瓷土_高177長105寬45cm_2022a

徐永旭_2022-13_高溫陶_高91寬82深21cm_2022a

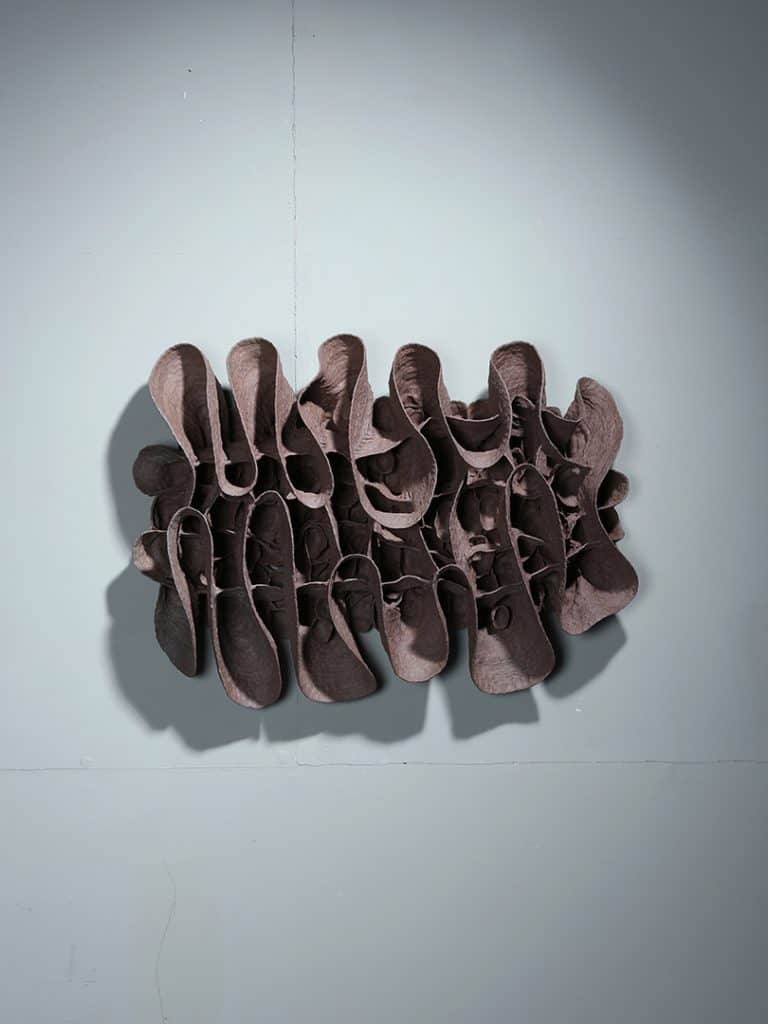

徐永旭_2022-12 高溫陶_高56寬74深18cm_2022a

徐永旭_2022-11_瓷土_高72寬70深14cm_2022b

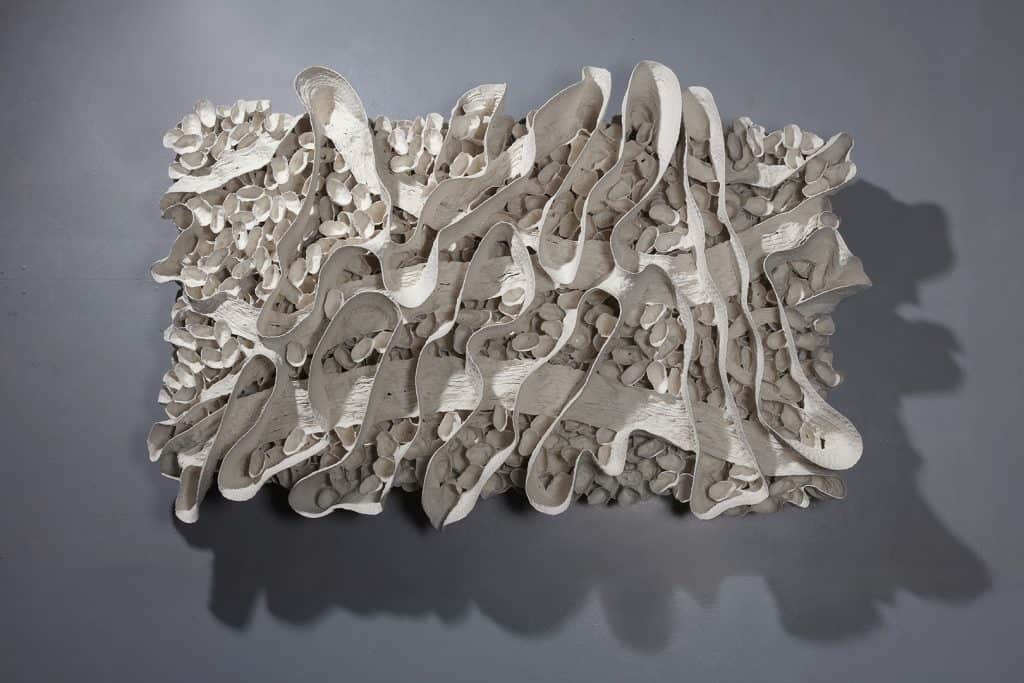

徐永旭_2022-10_瓷土_高31長60寬57cm_2022b

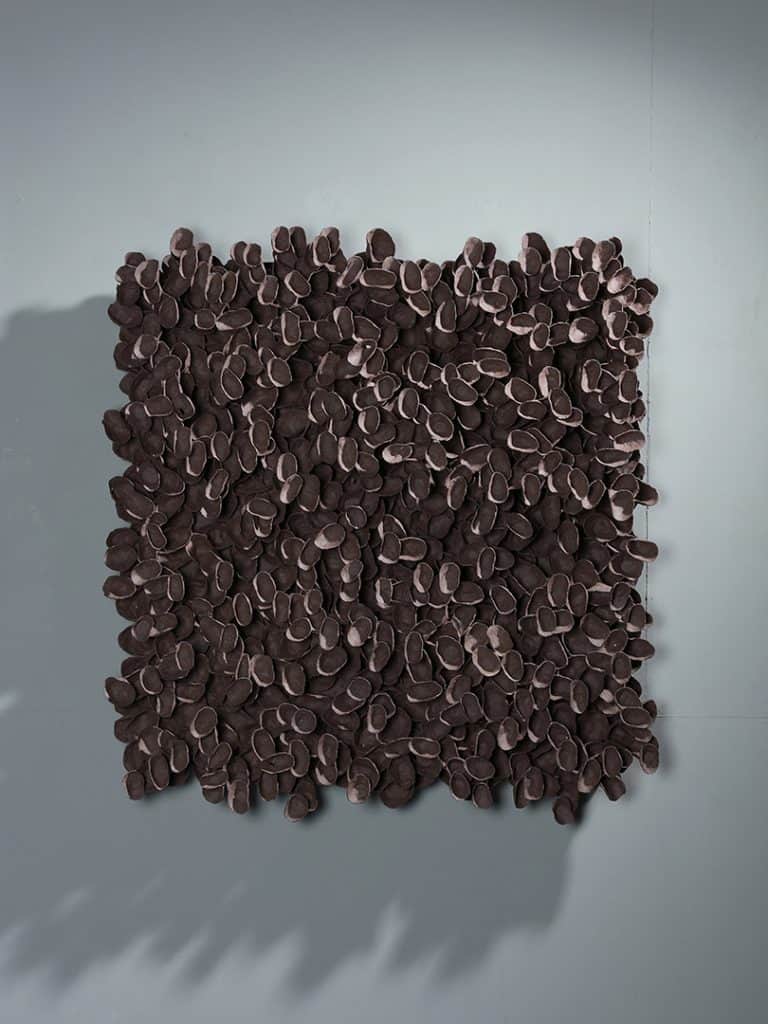

徐永旭_2022-1_瓷土_高116寬175深28cm_2022a

徐永旭_2021-22_高溫陶_高194長160寬130cm_2021b

徐永旭_2020-36_瓷土_高55長64寬57cm_2020

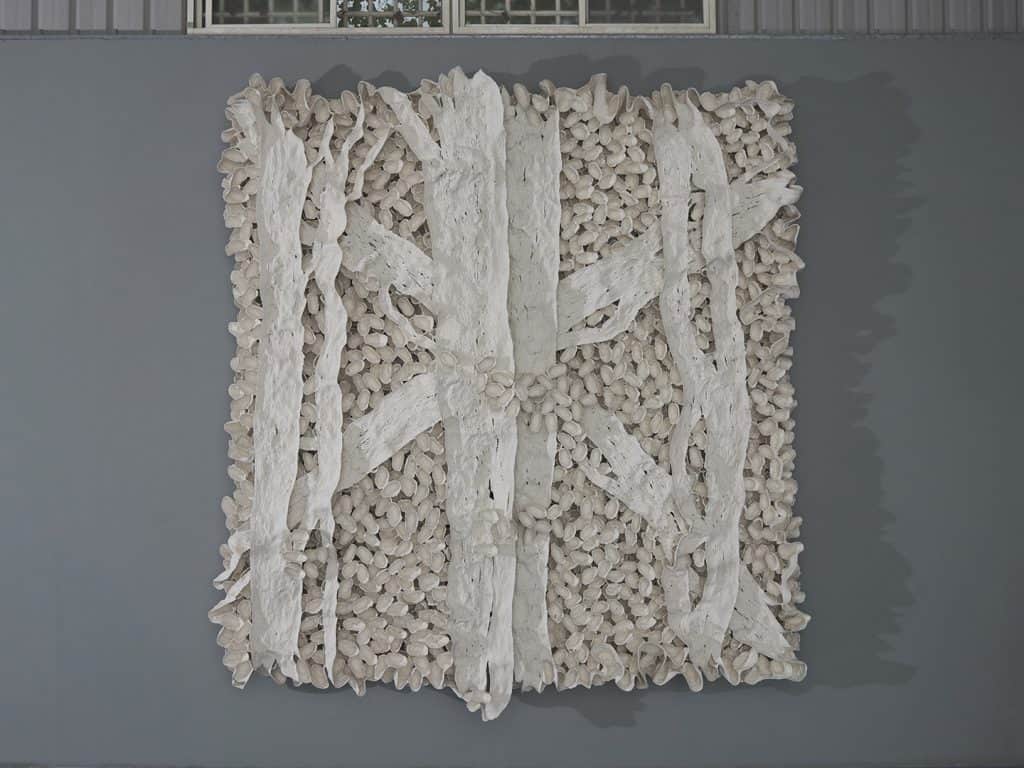

徐永旭_2020-9_瓷土_高302寬287深38cm_2020a

徐永旭_2019-33_高溫陶_高156寬303深33cm_2019b

徐永旭_2022-8_瓷土_高40.5x長27.5x寬24.8cm_2022

徐永旭_2022-7_瓷土_高23x長82x寬40cm_2022(1)

徐永旭_2022-6_瓷土_高70x長38x寬33cm_2022

徐永旭_2022-5_瓷土_高38x長29x寬20cm_2022

徐永旭_2022-3_瓷土_高76.5長49.5x寬44.5cm_2022(1)

徐永旭_2022-2_瓷土_高35.5x長71x寬58cm_2022

徐永旭_2021-26_瓷土_高61.3x長59.5x寬 46.5cm_2021

徐永旭_2021-25_瓷土_高61.5x長44x寬43cm_2021(1)

徐永旭_2020-25_高溫陶_高43x長59x寬 47cm_2020(1)

徐永旭_2019-36_高溫陶_高41x長29x寬23cm_2019